The Rationale

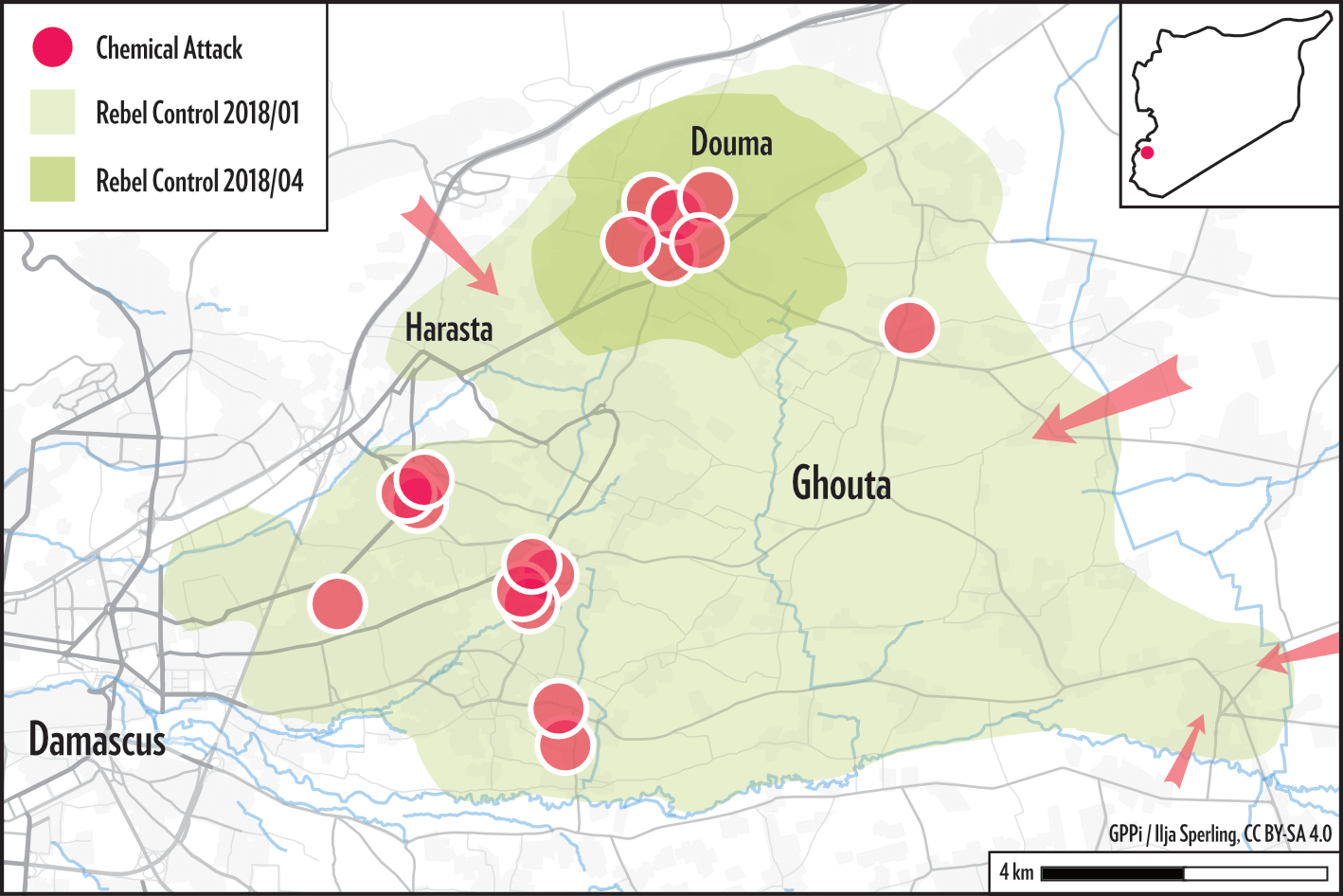

The war progressed and the Syrian government went on the offensive across the country, recapturing Aleppo in 2016 as well as swaths of territory in central Syria in 2017. In January 2018, after the failure of Russian-sponsored political negotiations, Assad and his allies prepared to bring down rebel-held Eastern Ghouta, just outside Damascus. Home to hundreds of thousands of residents and internally displaced civilians, the pocket had remained a symbol of unbending resistance to the Syrian regime in hearing distance to its seat of power.

Over the following three months, the regime and its Russian allies pursued a devastating three-track strategy of intense indiscriminate violence, ground offensives, and parallel negotiations for so-called reconciliation agreements – surrender deals in all but name. In rapid succession, settlement after settlement across Eastern Ghouta surrendered under the cumulative weight of years of siege and the overwhelming disproportionate and indiscriminate violence of the offensive.

Duma 2018: Breaking the Will to Resist

Duma, an early opposition stronghold, was the city that resisted the longest, as local rebel groups were hoping to hold out long enough to force a favorable deal with their Russian interlocutors. But despite their military prowess on the frontlines, it was the fate of civilians that in the end would force their hand.

As towns along the periphery of Eastern Ghouta fell to government forces, growing numbers of civilians moved deeper into Duma, putting additional strain on limited resources. Food and water were scarce. Medical centers were overworked. 1 For protection, most residents crowded into basements, which were not designed for hosting people for prolonged periods of time, thus leading to the spread of disease.

But they knew that whatever little protection these shelters afforded was limited – heavier than air, chemicals would still find their way into the hiding places. In such cases, civilians would have been better off moving to higher ground where they would be exposed to the conventional bombing. The combined use of conventional and chemical bombs had left civilians nowhere to hide.

“It is obvious that in the case of any bombardment, people would descend into shelters, whereas in the case of the chemical attack, the initial procedure was to go to a high location. This basic information is not known to all people, and even if you are aware, there is no way to know the type of attack before or at the moment of occurrence.” 2

Besides the physical uncertainty, the attacks had disastrous psychological effects on people. While chemical weapons accounted for an extremely small share of all munitions launched at Eastern Ghouta (local first responders counted more than 23,000 projectiles and only 19 chlorine attacks), survivors of the siege report that fear and rumors of imminent gas attacks were widespread among civilians, many of whom had been traumatized by the devastating Sarin attacks that took place in the area in August 2013. One activist from Duma recounted how residents would talk morbidly about the prospect of dying from shelling or gas: “[Civilians] used to say that death by chemical weapons [was] a merciful death” because it would at least leave the body whole. Another activist called it “death without blood” – depicting entire families suffocating silently in their sleep.

“The regime’s use of chemical weapons has been systematic in Eastern Ghouta since its beginning. The goal was always to target civilians. This also applies to conventional weapons and the siege of the region which targeted civilians economically, psychologically and morally.” 3

According to the journalist, the government’s rationale behind targeting civilians was to put pressure on military opposition groups to leave the area. As long as rebel factions were in charge, the regime would continue bombing civilians, perpetuating the hopeless situation. A representative of one of the military groups agreed: “[W]hen the regime was unable to control strategic areas, it used civilians to put pressure on us. In other words, when the regime was unable to penetrate the fronts, it wanted to take revenge on the civilians so that they would demand military groups to leave the region.” The approach worked: civilians directed their frustration at the rebel groups. Residents risked their lives, staging demonstrations in the city during brief interludes between shelling, demanding a negotiated settlement. With every attack, their calls grew louder and the pressure mounted.

On 7 April 2018, a final devastating chemical attack struck the city of Duma, killing at least 43 and injuring more.

As international investigators would later establish, around 7:30 pm and amidst a torrent of conventional bombardment, a helicopter took off from Dumayr Airbase and dropped a chemical munition on a residential building that served as a shelter for dozens of local residents. With the munition lodged on the roof of the building, the gas slowly poured down the stairwell, killing the dozens of residents who had instinctively – or out of habit – tried to flee toward higher ground. Meanwhile, the shelling remained so intense that it took first responders an hour to reach the building located only hundreds of meters away. Later that night, locals found a second munition that had landed in a second building.

“I went down to the bunker, and the sight of the massacre started becoming clearer. There were dead bodies of children tossed around and foam was covering their mouths. I couldn’t last more than three seconds, as my nose started running and my eyes tearing up, and I lost my balance. My friend pulled me out quickly, and we went to the medical station where I received first-aid. I washed my face with water and was sprayed.” 4

Just hours later, local rebel fighters agreed to surrender.

The following day, the city surrendered under a Russian-mediated “reconciliation” agreement. The head of a women’s center in Eastern Ghouta described this final attack as “the knockout, after which we left the area. In order not to repeat the 2013 massacre, we had two choices: either to go to the regime or to the north of Syria.” According to the Russian military, 21,145 militants and civilians departed from Eastern Ghouta’s largest city for rebel-held northern Syria. Overall, 67,680 individuals across the pocket chose to flee rather than reconcile with the government. Twice that number were sent to IDP camps operated by the regime.

To some, this final attack came as a surprise – until that point, they had hoped to receive help from the international community. As a worker for the Syrian Arab Red Crescent in Duma articulated: “We thought that the international community would not allow chemical use again, especially at such a stage.” The missile strikes against government sites launched by the US, the UK and France in response to the April 7 attack did little to change the locals’ perception that they had been abandoned. An activist explained that the Syrian regime’s apparent freedom to use chemical weapons had led locals to the collective realization that “nothing and no one will protect civilians from the violence and brutality of the regime,” leaving surrender or death as the two realistic outcomes.

The Operational Logic: Targeting Communities

In Duma, the Syrian government successfully employed chemical weapons to terrorize and break the backs of the local insurgency by targeting the population that sustained them. This is a key pattern of the Syrian government’s military strategy over the years.

Rather than attempt to target frontline troops or military positions, chemical weapons were repeatedly directed at a handful of communities known to be opposition strongholds. That is, towns that fighters call home, where they find moral support and physical protection, where the civilian population backs the insurgency. Together, the five towns most heavily hit with chemical weapons over the course of the war account for 25 percent of all attacks – the ten most heavily hit towns account for 40 percent.

Idlib 2015: Punitive Bombing in Defeat

The Damascus School of Counterinsurgency

While the Syrian regime’s approach of indiscriminately targeting opposition strongholds with chlorine had little immediate effect on the day-to-day movements of frontlines, it made perfect sense in the context of the regime’s overall military strategy.

Short on manpower and resources, and resting on a precarious foundation of sectarianism and rentierism, the regime and its backers pursued a military strategy of collective punishment against populations supporting or hosting insurgents. Unlike “hearts and minds” doctrines favored by contemporary western democracies, this approach to counterinsurgency – sometimes referred to as “draining the swamp” – does not seek to win over oppositionist populations through compromise or provision of services. Instead, it aims to inflict such unbearable pain that locals are forced to either withdraw their support from insurgent groups or flee areas outside regime control, thereby undermining rebel governance and facilitating government population control through aid provision.

In 2012, the Syrian regime thus began escalating its military strategy of indiscriminate violence against those parts of the countries that had over the previous year shaken off regime authority. 5 Beginning in May, the SyAAF began flying regular bombing missions against densely populated cities, such as Homs. In August, barrel bombs made their first appearance in Aleppo province. The first recorded chemical weapons attack attributable to the Syrian government happens later that year, again in Homs.

According to data collected and verified by the Violations Documentation Center in Syria (VDC), 92 percent of victims of indiscriminate modes of violence – bombing, gassing, sieges – were civilians. In line with the operational patterns described earlier, conventional and chemical attacks went hand-in-hand. For example, one Syrian refugee who made it to Jordan recounted to Handicap International how, during a major chemical attack on the neighboring village, residents who “saw rockets” had hid in their basements “in fear of the walls collapsing on them” – only to suffocate from the heavy gas. In multiple instances, Syrian government and Russian jets would bomb hospitals just after receiving victims of chemical attacks.

Thus, despite the frontlines hardening over time, the civilian death toll continued to climb: the share of civilian casualties due to indiscriminate violence jumped from 4 percent in 2011 to 48 percent in 2012, peaking eventually at a stunning 88 percent in 2017. Women and children were especially vulnerable to the bombing of residential areas. Their share among civilian dead almost tripled from 13 percent in 2011 to a peak 38 percent in 2016.

Under such violent conditions, peaceful civilian life outside the control of Syrian regime forces became all but impossible. In April 2012, a year after the outbreak of the uprising but prior to the escalation in indiscriminate shelling, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that 65,000 Syrians had fled to neighboring countries. Eight months later, that number would grow more than thirteen-fold to 750,000.

Displacement patterns trace not only the movement of frontlines, but also the intensity of violence. An overwhelming number of people ran from areas that were outside government control but within reach of its air force or long-range artillery. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), indiscriminate violence against populated areas was the primary driver of Syrians fleeing. At the time of writing, an estimated half to two-thirds of Syria’s pre-war population have been internally or externally displaced.

Thus, even as the Syrian government continued to lose ground to rebel forces on the frontlines, it was succeeding at the political goal of separating insurgents and civilian populations. This is why, even at its lowest point during the Idlib offensive of 2015, it continued to prioritize collective punishment of civilian populations over close air support to its own troops. Its primary pursuit was not the control of territory, but the creation of a comparative stability or safety advantage for areas loyal to the government. Compared to the violence, destruction and governance vacuum of rebel-held Syria, the government of Bashar al-Assad appeared stable and dependable.

Importantly, the Syrian regime also succeeded at linking the violence suffered by civilians in opposition-held areas with the presence of armed rebels. A representative survey of attitudes among refugees in Turkey showed that Syrians who had directly suffered indiscriminate violence – in this case, they had lost their home due to a barrel bomb strike – were significantly less likely to support opposition forces. Instead, they disproportionately chose to renounce all armed actors altogether. These effects were especially pronounced among women – anchors of civilian life whose withdrawal of support can have outsized effects on insurgent resolve. In our interviews, rebel commanders agreed that it was not their inability to hold off regime ground offensives, but their failure to protect civilians from violence that broke their backs.

Damascus was further able to translate the cumulative attritional effects of the strategy into political currency. A second survey showed that Syrian refugees who came from neighborhoods that had experienced violence and loss were, depending on how the question was framed, up to twice as willing (71 percent) to accept a compromise settlement with the Syrian regime than those from areas left untouched (35 percent). The closer the violence, the more likely an individual was to support reconciliation.

Conclusion

In Syria, chemical weapons were not the only, nor even the principal, type of mass violence unleashed against civilians. However, the government’s campaign of chemical weapons use represented a legitimate lynchpin around which it would have been possible to build international consensus for serious action for the protection of civilians and the containment of some of the worst fallout of a war whose shockwaves have rippled throughout the region and world.

As we argue, decisive action would have been most impactful in the aftermath of the Hama offensive of 2014, when it had become clear that diplomatic means alone were insufficient to curb even the worst excesses of the Syrian government. The international community had the opportunity to intervene and shape the war at its most decisive stage. A single salvo against the regime’s helicopter fleet or improvised munitions factories would have delivered a meaningful blow against the Syrian regime’s chemical weapons complex as well as its entire machinery of indiscriminate violence. But even though international powers chose to stand aside then, it is never too late to reimpose meaningful costs for the use of proscribed weapons: Syrian government forces employed chlorine as a weapon as late as 2019 in an offensive in northwestern Syria, where today more than two million civilians huddle in fear of the worst violence of the war.

As our analysis shows, the regime’s barrel bombing and chemical campaign had little direct effect on the movements of frontlines. Its disruption could have prevented – or slowed – regime victory without leading to the regime’s immediate collapse. The subsequent experience of retributive strikes following the chemical attacks of Khan Shaykhun in 2017 and Duma in 2018, in a much more contentious regional environment, showed that the threat of escalation could easily have been contained. This point should be taken especially seriously by European governments concerned about refugee flows and ungoverned spaces. Early disruption of the regime’s war effort could have limited one of the principal drivers of civilian flight and governance failure.