1. Introduction

Our team at the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi), together with local and international partners, has built the most comprehensive dataset on reported incidents of chemical weapons use in Syria to date. The analytical findings we can draw from the data are the main subject of our 2019 study ( Nowhere to Hide ) as well as an interactive web essay that is part of a more comprehensive online resource on the topic, published in 2020. This methodology note will focus on how we have built and organized the dataset that forms the empirical foundation of our work. In addition, it outlines our analytical approach to understanding the Syrian chemical weapons complex.

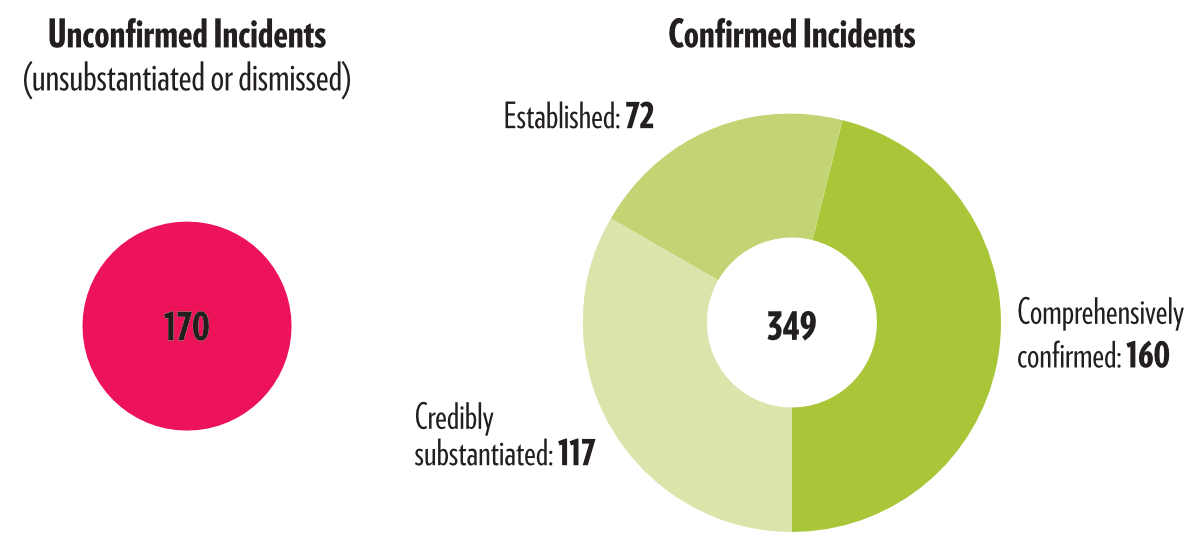

As of May 2020, and out of 519 reported attacks, we are able to classify 349 attacks as either credibly substantiated, established or comprehensively confirmed. These incidents – assessed with varying degrees of confidence – form our dataset and the number is set to rise as our small team of researchers continues to unearth and introduce additional data.

Working with data from an active war zone means dealing with gaps and inconsistencies in documentation, some of which may be driven by political interests or individual agendas that underpin reporting on the topic. All of this presents us with significant challenges in our undertaking to build a credible dataset. We consider it important to be transparent about the steps that we have taken to try to mitigate potential gaps and biases. This methodology note attempts to explain these processes while still protecting the confidentiality of sources. The latter has also informed our decision not to include some of the data we have received in the public dataset that is available for download. 1

In addition, our intent for this note is for it to serve as a basis for exchange with other researchers and experts who may have pertinent information or experience to contribute as we make our dataset available to activists, analysts, government officials, and anyone else affected by or interested in the use of chemical weapons in Syria. We hope to jointly take on the enormous challenge of documenting these war crimes as comprehensively as possible. 2

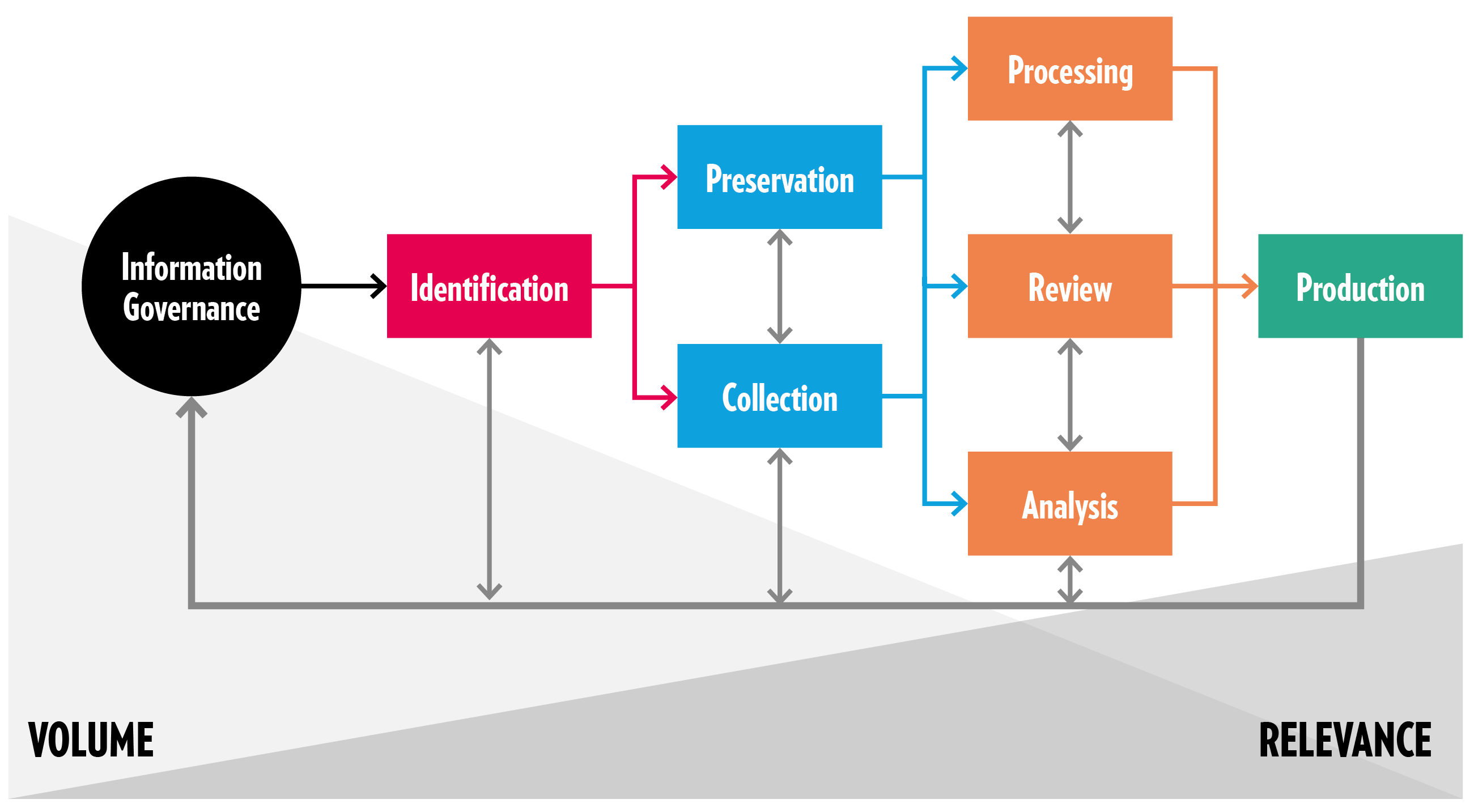

The structure we have chosen for this note loosely follows the Electronic Discovery Reference Model (EDRM, see chart below), which guides our workflow at GPPi. First, we will describe how we identify potential sources and collect and preserve evidence. In subsequent chapters, we discuss how we review, process and analyze the information thus obtained. This includes details on how we evaluate sources, build incidents, identify patterns, and attribute them to perpetrators. We conclude with an assessment of the gaps and limitations of our approach. While developed with a specific focus on incidents related to chemical weapons, we consider this methodology to be potentially applicable to the investigation of a variety of types of unlawful attacks committed in the Syrian war.

2. How We Identify, Collect and Preserve Evidence

Building an Evidence Base

The Syrian conflict is commonly described as the “best-documented war in history,” owing to the proliferation of smartphones and digital recording devices in recent years. The abundance of citizen-generated evidence offers human rights organizations, activists, journalists, and investigators insight into conflict areas where it would have previously been unthinkable. However, the sheer number of unlawful attacks and the estimated volume of available evidence means that, despite the vast potential, no organization had yet attempted to compile and process a comprehensive dataset on any type of unlawful attack witnessed in Syria – be it with chemical or conventional weapons.

Nonetheless, in building our dataset on the use of proscribed chemical weapons in Syria, our team at GPPi had the benefit of being able to draw on the experience and outputs of a number of local and international organizations − including the work of investigatory teams from the United Nations (UN) and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), who for years have been working diligently to document, analyze and, in some cases, even attribute dozens of individual chemical weapons incidents. While their investigations may not cover all chemical weapons attacks in Syria, their experiences identifying, collecting and analyzing evidence allows us to appreciate the range and limitations of both the evidence and analytical toolkit available to us.

In most cases of alleged chemical weapons attacks in Syria, we collect the relevant information directly from publicly accessible sources or via our networks of local and international partner organizations, who have agreed to provide us with information on the basis of signed “Memoranda of Understanding” (MoUs). These memoranda govern the transfer and storage of information as well as decisions about referencing and citation. At all stages, GPPi adheres to confidentiality agreements with our partners and prioritizes source protection above competing concerns. Thus, all sources identified in our publications or dataset are either publicly accessible or have explicitly agreed to be named.

As we rely on our partners to collect primary sources, we do not retain physical samples or specimens. This limits our own evidence preservation efforts to open sources. 3 To systematize this practice, we have partnered with Syrian Archive, an organization that collects, preserves and verifies hundreds of videos related to chemical weapons incidents in Syria. We will soon extend this partnership to also include images and social media posts.

Qualitative Research and Data on Military Deployments

In addition to the incidents data compiled and preserved in our dataset, our research and analysis of the use of chemical weapons in Syria draws on a range of qualitative and quantitative data covering important military and humanitarian aspects of such attacks. These include information on deployments and armaments of conventional Syrian military formations and armed groups, flight tracking data for military aircraft, displacement and polling data related to the impact of chemical attacks on the civilian population, satellite imagery for verification, and expert technical assessments.

Additionally, we inform our research and analysis through qualitative research via literature and interviews. The latter are conducted either through trusted partners on the ground or remotely by our team. Interviews with victims, witnesses, doctors, local council representatives, and representatives of rebel groups help us understand the behavioral patterns of all actors involved in or affected by these chemical attacks, and thus to substantiate our arguments and analytical results.

3. How We Review and Process Evidence

Source Evaluation

As we are unable to directly access the incident sites in Syria, we collect all of our data remotely from open sources or via partner organizations whose standards and methodologies for the collection, processing and analysis of evidence vary widely. Based on the experience of other investigative bodies and publications, there are three main dimensions in which we anticipate challenges to our dataset: impartiality (i.e., evidence that is part of a biased investigation or stems from an individual or group with partisan interests); authenticity (i.e., evidence that has been doctored, edited or tampered with in any way before it came into our possession); and reliability (i.e., the source is unknown or has provided false information in the past).

To screen our evidence for these three challenges, we evaluate the sources. That includes a review of each source’s collection, preservation and processing methodologies and procedures as well as verification and triangulation of the information they provide. In this process, we rely on three tools:

- play_arrow Methodology ReviewWe request that partner organizations share with us their methods and methodologies for collecting, preserving and processing evidence (including their evidentiary thresholds for attribution) alongside their data. Our team can then assess these methodologies against international standards and best practices (keeping in mind the inherent challenges of collecting and verifying evidence in a war zone).

- play_arrow Consistency Check

By cross-comparing information, we conduct tests to gauge the level of consistency between data that was provided by partners independently from one another. In this way, we can assess the degree to which their respective reporting overlaps (as well as, where applicable, to what extent it is in agreement with findings by the UN and the OPCW). In cases where reporting on an incident is highly consistent across sources, such consistency could conceivably compensate for a weak assessment from the methodology review process (e.g., an instance in which we found a source’s formal evidence collection methodology to be underdeveloped or intransparent).

At the same time, our researchers are conscious of the limitations our partners face given the difficult environment in which they operate as well as of the fact that their mandates may be limited. Cases of consistent, unexplained disagreement may lead us to downgrade or even dismiss a source, meaning that the evidence it has collected will carry less or no weight in our confidence calculations (for details on how we calculate confidence scores, see Classifying Incidents by Confidence Level). However, in most cases, disagreement between sources is cause for investigation rather than dismissal. For example, medical charities will naturally only be able to confirm an incident when it produced casualties that were treated in their facilities. Civil defense units, on the other hand, can respond to – and thus record – incidents in remote areas that would otherwise have remained undocumented. In addition, they can recover debris from unexploded munitions.

- play_arrow VerificationIn some instances (e.g., in the case that incidents on first review appear to contradict established patterns, inconsistencies, or evidence by sources that work without consistent methodologies), we may manually verify specific pieces of evidence. In most cases, the research team will be able to verify a piece of information either through other closed sources or via available open source verification methods. In rare instances, we may need to consult external experts whose assessments will complement the existing body of evidence.

While we do apply these tools in a systematic way, source evaluation remains a complex and at times subjective task. Even within organizations, methods can evolve over time or vary according to the context. Our estimates of sources’ impartiality, authenticity and reliability thus represent summary judgments that may be qualified or supplemented in individual instances, where appropriate.

Source Categorization

We factor the results of the source evaluation into our dataset by sorting each source into one of four categories: (1) authoritative; (2) primary; (3) secondary; and (4) open sources. This categorization then forms the basis for our calculation of confidence levels for reported incidents. The table below provides a list of sources grouped according to their category.

We consider a source authoritative when its methods and procedures meet the highest international standards for investigations – that is, when evidence is collected and analyzed by impartial, experienced, international staff that operates under an international mandate. In practice, these are bodies of the UN and OPCW who are able to conduct interviews with victims or witnesses as well as other actors on the ground, collect documentation such as victims’ clinical or autopsy files, are mandated to collect environmental samples as well as tissue samples of those killed or injured by an attack, and who can review munitions or munition remnants recovered from attack sites.

Among our primary sources, we count groups and individuals that are either directly involved in the response to chemical weapons attacks on the ground or who otherwise collect unprocessed information about reported incidents from those involved (e.g., specialized INGOs such as Conflict Armaments Research). With most of these groups, we have collaborated for years and have signed MoUs. We have reviewed their methodologies and understand the context in which they operate, which allows us to most accurately judge the reliability of their reporting.

Where available, we also review secondary sources, i.e., sources that process and sometimes verify information and pertinent evidence (including from witnesses that we or our partners could not directly access). However, these sources are not directly involved in the collection of evidence on the ground. They also differ in their reliability and, accordingly, weigh differently when factored into our calculation of confidence levels. We include in this category international and local civil society and human rights organizations that provide assessments of incidents, as well as international, regional and local media spanning a wide range of perspectives and editorial standards. These also include outlets that are close to the Syrian government or opposition as well as their respective backers.

To improve our understanding of individual incidents, we additionally search for evidence via open sources on YouTube, Facebook and Twitter. In particular, we look for relevant social media posts from local news outlets as well content shared by regular citizens on the ground, who are often the first to know about an attack and report on it after it has taken place. We especially seek out posts that include videos or images that may aid us in verification. We have also partnered with Syrian Archive, whose verification of visual documentation helps us corroborate alleged attacks.

Given social media platforms’ low threshold for access as well as the prevalence of disinformation on these sites, an open-source post alone does not meet our threshold for consideration as evidence by a secondary source. Instead, we count it as a standalone category that has a lower weight when factored into a calculation of the confidence scores for an incident. Some social media posts may add a qualitative dimension to our understanding of an incident, but otherwise fall short of our threshold. These are collected and stored but do not count as part of the open sources we include in our calculations.

- play_arrow Typology of Sources

Authoritative - UN-OPCW Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM)

- OPCW Fact-Finding Mission (FFM)

- OPCW Investigation and Identification Team (IIT)

- Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (COI)

- United Nations Mission to Investigate Alleged Uses of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic

Primary - Syrian American Medical Association (SAMS)

- Independent Doctors Association (IDA)

- Individual physicians and medical practitioners

- Mayday Rescue and the White Helmets (Syria Civil Defense)

- Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR)

- Local Coordination Councils (LCC)

- Violence Documentation Center (VDC)

- Chemical Violations Documentation Center for Syria (CVDCS)

- Conflict Armament Research (CAR)

- Trusted individual sources 4

- …

Secondary - Bellingcat/Brown Moses 5

- International media

- Regional media

- Local media

- Free Syrian Army (FSA)

- National Syrian Council (NSC)

- French Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs (FRA MFA)

- Human Rights Watch (HRW)

- Siege Watch (PAX)

- Institute for the Study of War (ISW)

- Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ)

- …

Open Source - YouTube

- …

Variables

To understand the full chain of events related to individual chemical attacks in Syria, we have defined 15 variables (such as the date and time of the attack, the chemical agent, or the method of delivery of the respective munition) that help us structure the information we have collected for each reported incident via the sources outlined above.

- play_arrow Variables and Their Values

Each value additionally contains the value “NA” (not available) for missing information.

Variable Values Confidence Level 0-3 Date YYYY-MM-DD Time 00:00:00 – 23:59:59 Locale 129 unique places Governorate - Aleppo

- Damascus

- Daraa

- Deir Ez Zor

- Hama

- Al-Hasakah

- Homs

- Idlib

- Latakia

- Quneitra

- Raqqa

- Reef Damascus

- As-Suwayda

- Tartus

Theater - Aleppo

- East

- Homs

- Northwest

- South

- Wider Damascus

GPS Coordinates - Long 0.000000

- Lat 0.000000

- NA

Military Campaign - Damascus Offensive

- Hama Offensive

- Idlib Offensive

- Battle of Aleppo

- Eastern Ghouta Campaign

Delivery - Aircraft

- Ground-launched

- Helicopter

Munition Type - Barrel/canister

- Grenade

- Missile

- Other

- Sarin bomb

- Sarin grenade

- Shells

Chemical Agent - BZ

- Chlorine

- Other

- Sarin

- Sulfur Mustard

Killed 0-9999 Injured 0-9999 Perpetrator - Syrian government

- Rebels

- ISIS

In cases where sources disagree in their reporting on the nature of a specific variable (for example, the number of people injured by an attack), we enter into the dataset the information provided by the most reliable source available for any given information type. We assess a source’s reliability through our source evaluation and categorization process (outlined above). When two similarly reliable sources differ in the information they provide on a specific variable, we decide which information to use by the level of details provided in the respective reportings. We do not include inferences in the dataset.

Incidents form the foundation of our dataset. However no commonly accepted definition of what constitutes an “incident” exists. The comparatively small number of chemical weapons attacks in Syria means that, in most cases, there will be little ambiguity as to what constitutes a single “incident” or attack (i.e., single air delivery or ground-launched barrage) per location. Accordingly, an adequately restrictive definition could define a single incident as an event where munitions carrying chemical agents impact within a radius of 1,000 meters and a time period of 120 minutes or less. Alternatively, when time of day or impact radius prove difficult to establish, incidents could also be identified by delivery vehicle – either a single airframe (e.g. Mi-8/17 helicopters commonly carry two chlorine canisters) or the point of origin of a barrage. In cases where none of that information is available, researchers err on the side of caution and collapse potential attacks into single incidents, which will be expanded as more detailed data becomes available.

- play_arrow Confidence LevelFor each incident we calculate a confidence level according to the classification outlined below. The values are:

- 0 : incidents that are unsubstantiated or were dismissed;

- 1 : incidents that are credibly substantiated;

- 2 : incidents that are established;

- 3 : incidents that are comprehensively confirmed.

- play_arrow DateWe associate a specific date (value: YYYY-MM-DD) with each reported incident in our dataset. While the great majority of incidents are unequivocal in their dating, there are cases where sources report conflicting dates – this occurs most often for nighttime attacks.

- play_arrow TimeWhen available, we assign a specific time (values: 00:00:00–23:59:59 local time) to the incident. In instances where two credible sources contradict each other, we decide by the level of detail provided. In rare cases, we may attempt to establish the precise time via verification methods (e.g., by determining the time that a tweet was sent or through the estimated time of day captured in a video).

- play_arrow LocalityWe break down an incident’s location into three different variables: locale, GPS coordinate and governorate. The locale specifies the smallest identifiable settlement – i.e., the village, district or town – that was hit (values: 129 unique places). Each incident is associated with GPS coordinates of the smallest settlement with identifiable coordinates (derived from GeoHack via Wikipedia) − with the exceptions of some subdistricts of bigger cities, namely Aleppo and Deir Ez Zor (values: latitude and longitude). Each settlement lies within one of the 14 Syrian governorates.

- play_arrow Theater & CampaignFor analytical purposes, we further categorize each incident according to one of six theaters of the Syrian war (values: Aleppo, East, Homs, Northwest, South, and Wider Damascus). In addition, where possible, we associate the incident with a specific military campaign (values: the Damascus Offensive in 2013, the Hama Offensive in 2014, the Idlib Offensive in 2015, the Battle of Aleppo in 2016, and the Eastern Ghouta Campaign in 2018).

- play_arrow Delivery MethodWhere available, we have recorded information pertaining to the delivery method (values: air- or ground-launched) as well as munition type (values: barrel/canister, grenade, missile, Sarin bomb, Sarin grenade, or other). With the exception of the Sarin bomb and Sarin grenade, these munitions represent a breadth of munitions employed by the Syrian government or the Islamic State (a munitions typology is forthcoming). Naturally, the two variables are mutually dependent. Our assessment of the type of airframe is based on the descriptive account in the source. While descriptive accounts may be mistaken, the number of airframes available to the Syrian Arab Air Force (SyAAF) that can deliver chemical weapons is very small − and such distinctions tend to be readily visible to observers. Because of that, in most cases, descriptive accounts can be judged as fairly reliable. However, in light of these restrictions, our public dataset only features the values barrel/canister, missile, and other. The remaining munition types will, for the time being, only inform internal analyses.

- play_arrow Chemical AgentWith regard to chemical agents, our dataset includes four values: chlorine, Sarin, Sulfur Mustard, and 3-Quinuclidinyl Benzilate (QNB, also known as “BZ”). The designation is based on reporting from available sources as well as, in some circumstances, from pathology reports about victims that are accessible via open sources or other qualitative evidence.

- play_arrow CasualtiesOur dataset also reflects the number of casualties produced by an incident, which is divided into people killed and people injured. The variable can take on infinite values and starts with zero for incidents that led to no injuries or deaths. Incidents for which no information about casualties is available are assigned the value “unknown”. It is often the case that reports diverge on casualty numbers. Again, we resolve this by reverting to the most reliable source. We also assume a high error probability for the number of people injured, thus taking into account the reality of (mis-)counting casualties during the chaotic aftermath of an attack.

- play_arrow PerpetratorFinally, we include the presumed perpetrator for each incident (value: Syrian government, ISIS, rebels). In cases where neither our authoritative nor our primary sources were able to attribute the attack, we assign responsibility on the basis of the associated attack pattern in accordance with our pattern analysis and attribution approach (outlined below).

Classifying Incidents by Confidence Level

As we fill the variables and produce the dataset, we assign a specific confidence score to each individual incident. This score is calculated on the basis of our source evaluation and categorization. Each incident’s score is a function of the number and quality of the available sources and may thus evolve as the evidence base that underpins the dataset expands. Ultimately, it represents an imperfect quantification of the likelihood that a reported chemical weapons attack has taken place and that it has occurred as described by our sources. As such, it is an attempt to be both consistent and transparent in our evaluation of incidents. On the basis of the assessed evidence base, we classify all incidents into four confidence levels, ranging from 0 to 3.

- play_arrow 0 : Unsubstantiated or DismissedThese are reported incidents that either did not meet the basic threshold of plausibility, were investigated by competent international bodies and subsequently dismissed, or for which the available sources failed to meet our criteria for a higher score.

- play_arrow 1 : Credibly SubstantiatedThese are reported incidents that were corroborated by at least one primary source of evidence or two or more secondary sources or videos and images.

- play_arrow 2 : EstablishedThese are reported incidents that were backed up by at least two primary sources of evidence, or one primary and two secondary sources.

- play_arrow 3 : Comprehensively ConfirmedThese are reported incidents that were investigated and confirmed by at least one authoritative source, backed up by at least three primary sources of evidence, or corroborated by two primary and two secondary sources.

Given the practical challenges of collecting evidence on an ongoing conflict as well as the inherent limitations of designating values for the variables listed above, we occasionally reassess calculated confidence scores on qualitative grounds. As of April 2020, this is the case for 14 incidents – all of which have been downgraded for the sake of caution. 6

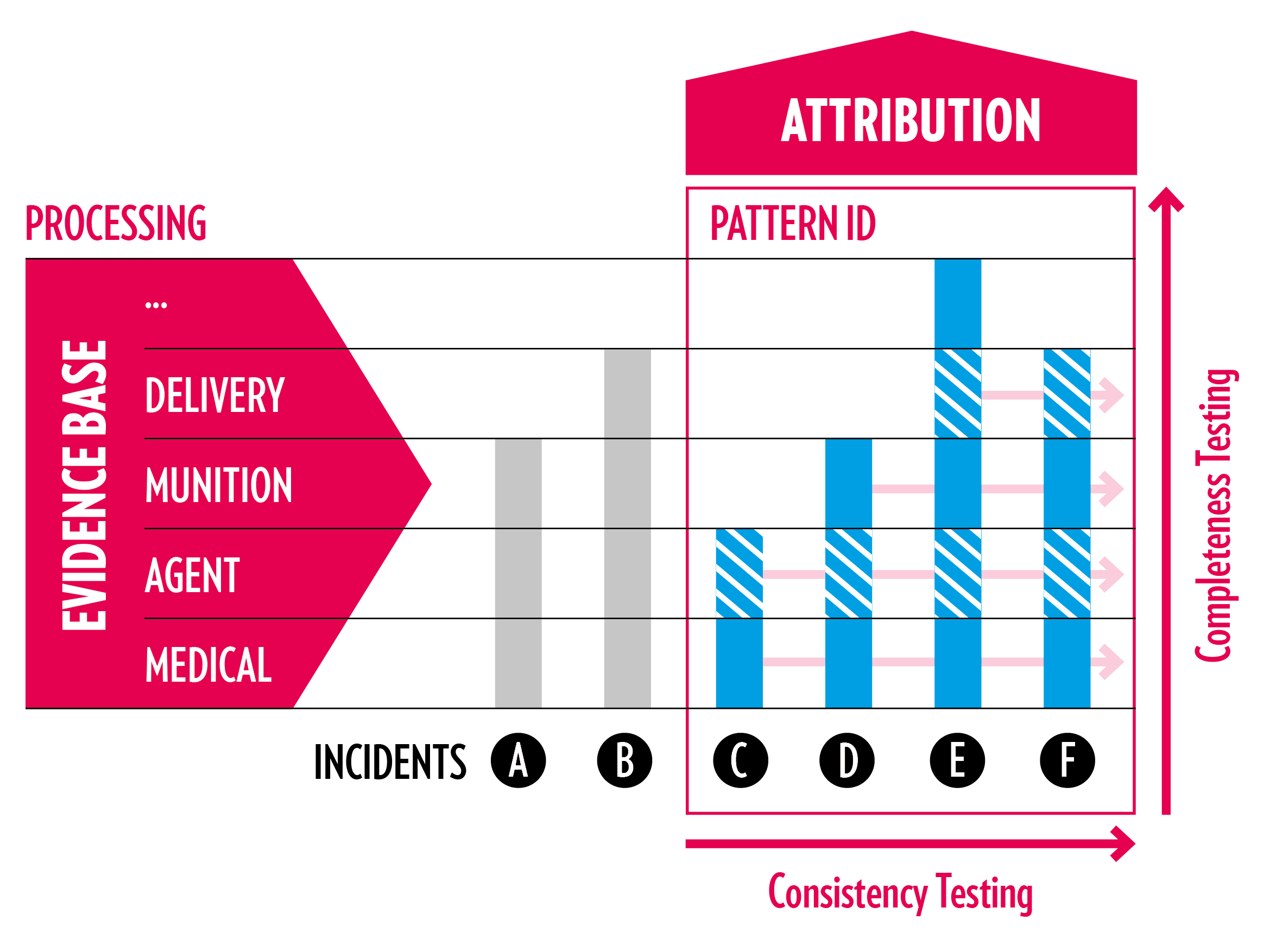

4. Attribution

Given the scale of the challenge (our dataset currently includes 519 reported incidents) as well as time and resource constraints, 7 we looked for ways to efficiently organize the task of attributing attacks to factions operating in the Syrian context. In doing so, we focused on well-established incidents with a high degree of similarity to other attacks, building a typology of attack characteristics. Thus, instead of attributing hundreds of chemical weapons attacks on a case-to-case basis, our research team has been able to analytically distill the attribution challenge from 349 or more credibly substantiated, established or confirmed attacks to a handful of identifiable attack patterns – and to attribute these patterns via a small number of “hinge cases” for which culpability can be established with relatively low resource investment effort by building on the prior work of the OPCW, the United Nations and others.

Identification and Attribution of Attack Patterns

By testing for consistencies in values across the dataset − i.e. by looking for corresponding qualitative characteristics between two or more incidents − we can systematically identify attack patterns. The more characteristics correspond across incidents and the higher the number of incidents for which this is the case, the clearer the pattern. In choosing variables around which to build our patterns, we prioritize characteristics for which there is consistent reporting and which have a high informative value with regard to attribution. In our experience, the ‘munition type’ variable is best suited for this purpose. In most instances, remnants of munitions are the first and most important pieces of material evidence recovered from attack sites. This is especially true in Syria, where almost all chemical weapons attacks, including those that involved highly volatile and dangerous nerve agents, were executed using domestically produced improvised and standardized munitions designs. Whether spent or intact, munitions tell us a lot about the nature and evolution of the Syrian chemical weapons program as well as its operational integration into the conventional Syrian war machinery. We start by filtering the data by one specific value for the variable munition type. We then subsequently deepen our pattern identification by testing for variables that are closely connected to munition types (such as chemical agent, delivery method, region, or military campaign) and that lead us toward attribution until we arrive at a clear typology of attacks that nonetheless leaves room for small context-specific variations and data gaps. During this process, we continuously compare intermediate results of our analysis with our understanding of the broader military and conflict-related developments throughout the Syrian war.

In our research, we have identified the following major attack patterns:

- Air-delivered improvised chlorine bombs of at least two generations (2014-2015 and 2016-2018);

- Ground-launched improvised chlorine rockets or IRAMs;

- Ground-launched improvised munitions carrying Sulfur Mustard;

- Dedicated air-delivered M4000 munitions carrying Sarin;

- Improvised grenades carrying Sarin;

- Other – A range of non-specific, usually improvised munitions used in a range of circumstances.

In order to attribute these patterns, we look for what we call “hinge cases” for each of the patterns. In selecting these cases, we prioritize attacks that have either been previously investigated and attributed by authoritative sources or score high both in terms of consistency (similarities with other incidents) and completeness (detailed information about the chain of events leading up to event). Identifying such incidents requires comparatively little investment in terms of additional work, but if investigated to completion they carry the potential for ripple effects, helping us understand other similar incidents throughout the dataset, particularly among lower-priority cases. 8

Evidentiary Threshold

In attributing hinge cases, we are sometimes able to rely on determinations made by authoritative sources, in particular the UN-OPCW Joint Investigative Mechanism as well as the OPCW Investigation and Information Team (IIT). In instances where neither body has assigned responsibility for an attack to a conflict party, we try to make our own determination on the basis of the available evidence and in accordance with the threshold of “reasonable grounds.” Indeed, the first report of the newly-established IIT has set a helpful precedent for the use of “reasonable grounds” as the evidentiary threshold for attribution. 9 The OPCW defines this as a “sufficient and reliable body of information which would allow an objective and ordinarily prudent observer to conclude that a person used chemical weapons with a reasonable degree of certainty.” In practice, this means that the investigations team “assessed this information holistically, scrutinizing carefully its probative value through a widely shared methodology in compliance with best practices of international fact-finding bodies and commissions of inquiry.”

5. Gaps and Limitations

While our dataset represents the most comprehensive account of chemical weapons attacks in Syria, our work was and continues to be subject to the inevitable access and data collection limitations that come with war. Some incidents that undoubtedly took place may not be represented, or only represented with a low confidence score because of a lack of access to data.

There are several factors that affect the overall availability of data as well as the variances in data between different regions of Syria. For one, military sieges, a lack of electricity and sporadic internet access, low population density, and poverty can all limit reporting, both in a region as a whole as well as in more localized pockets of terrain. In addition, restrictions on civil society and aid organizations and on free transfer across borders has also limited access in different regions, often for long periods of time. Reporting organizations may face restrictions or threats that prevent them from collecting data or documenting attacks, or they may face challenges in transmitting such information to locations outside of Syria.

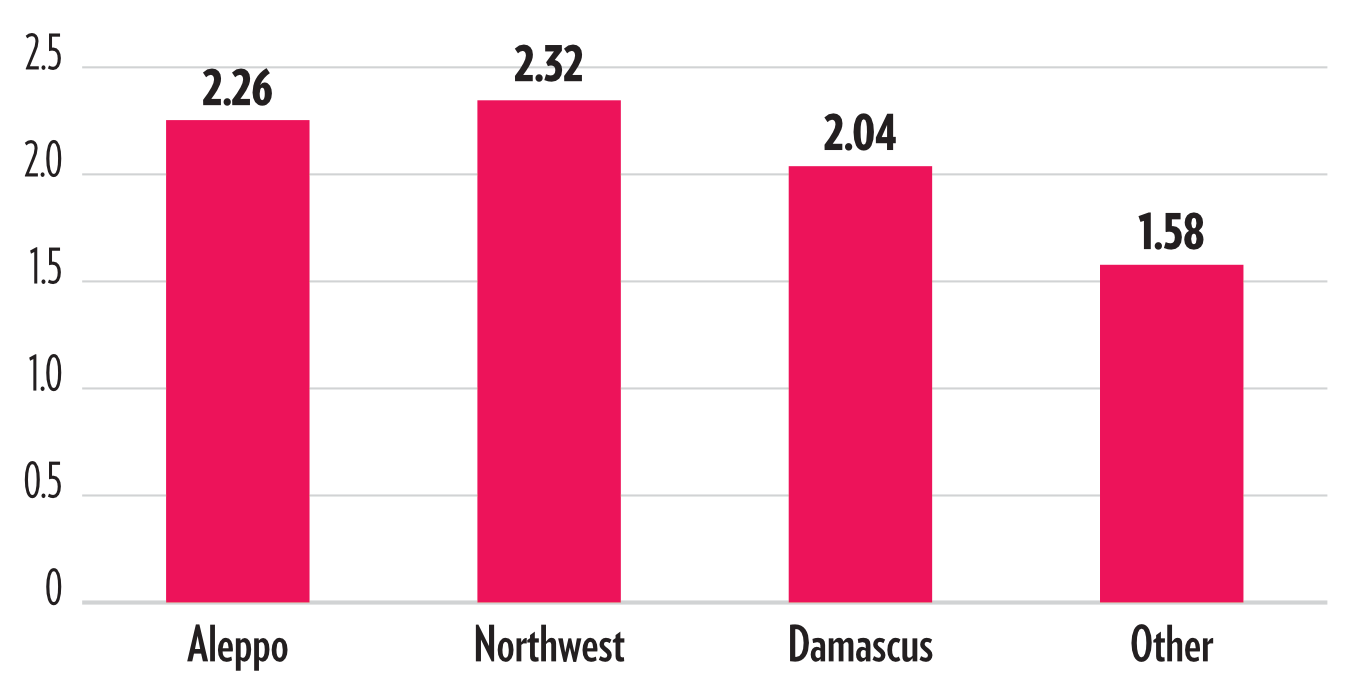

In our dataset, the Northwest and Aleppo regions, both of which offer cross-border access to Turkey and have an active civil society presence, account not only for the greater share of attacks but also have the highest average confidence scores among all the regions. On the flipside, we suspect significant underreporting in areas that restrict civil society access and cell phone use among the broader population. Most notably, this affects reporting from areas held by the Islamic State. Based on our analysis and from sporadic reports by underground activist networks in these regions, we suspect that Syrian government forces repeatedly used chemical weapons against populations in these areas during multiple military campaigns in central Syria in 2016 and 2017. In order to capture as many of these attacks as possible, we have gone to great lengths to incorporate information on individual incidents provided by trusted informant networks in these areas. However, these reports are infrequent and unlikely to have captured the full extent of the attacks.

Second, a lack of capacity among Syrian groups to detect chemical weapons attacks and preserve the respective evidence in the early years means that reporting on suspected attacks has become both more comprehensive and more reliable over time. Only in the aftermath of the devastating chemical attacks in Ghouta in August 2013 did international donors invest more consistently in the chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) protection and response capacity of Syrian first responders, doctors and civil society. As their general knowledge and technical capacity grew, reporting became more consistent and reliable.

Third, we have to accept that incidents without casualties are less thoroughly documented than those where first responders and medical staff are called in to save and treat victims, which generates additional evidence. In addition, local reporting or social media posts that document incidents involving casualties are far more likely to capture international attention and provoke further investigation. Moreover, munitions that landed in fields or other unpopulated areas, or whose payload did not disperse, sometimes remain undiscovered. On the other hand, we cannot rule out that some reported incidents may have been falsely documented as chemical attacks, for instance because some symptoms of chlorine intoxication, such as breathing difficulties, are not specific to chemical weapons alone.

- play_arrow Methodology:Introduction