The Logic

To understand how and why Syrian government forces used chemical weapons at this scale and with such persistence, we have identified patterns within our dataset. It is from both consistencies and outliers among the incidents that we can draw analytical inferences to provide the basis for a more comprehensive understanding of the role that chemical weapons have played in the Syrian conflict. As a first step, we scour the dataset for connections between attacks, which helps us reduce our massive dataset to a handful of identifiable attack patterns. We then draw on our knowledge of conventional military and humanitarian developments, supplemented by qualitative research, to place these patterns in the broader context of the Syrian civil war.

Connecting the Dots: Pattern Analysis

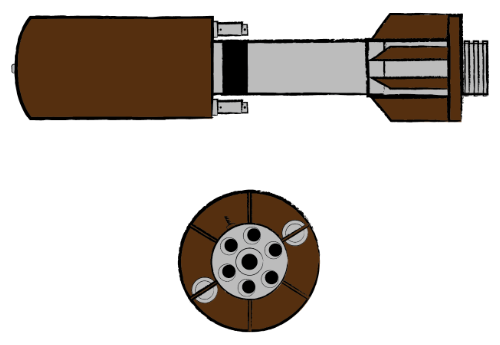

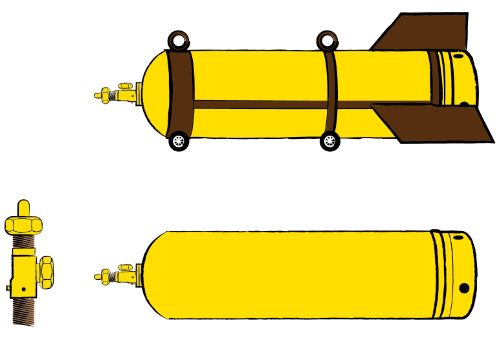

The first and most important material pieces of evidence recovered from most attack sites are remnants of chemical munitions. Whether spent or intact, these tell us a lot about the shape and evolution of the Syrian chemical weapons program. In addition to the forensic information gleaned by chemical and ballistics experts, we can review the specifications of dozens of these remnants to identify specific munition types. This approach is especially fruitful in Syria, where almost all chemical weapons attacks, including those involving highly volatile and dangerous nerve agents, were executed using domestically produced improvised munitions designs. Out of 349 incidents, only three are known to have involved Soviet-era munitions specifically designed for chemical warfare. 1

Improvised and Imprecise: Chlorine Munition Designs

Ground-Launched

Air-Launched

We take our munitions typology and map the appearance of these missiles and bombs in different places over the course of the war. For example, a simple geographic breakdown of broad munitions types employed in different theaters of war suggests a clear divide between Syrian forces leading the chemical campaigns in the Northwest and Aleppo region, where air-delivered barrel bomb-type designs account for 91 percent of all attacks, and the Damascus theater, where ground-launched missiles and mortar grenades account for almost the same overwhelming share. Exceptions to these rules, where formations normally associated with one type of attack appear on the other side of the country, help us narrow down our search for the culprit.

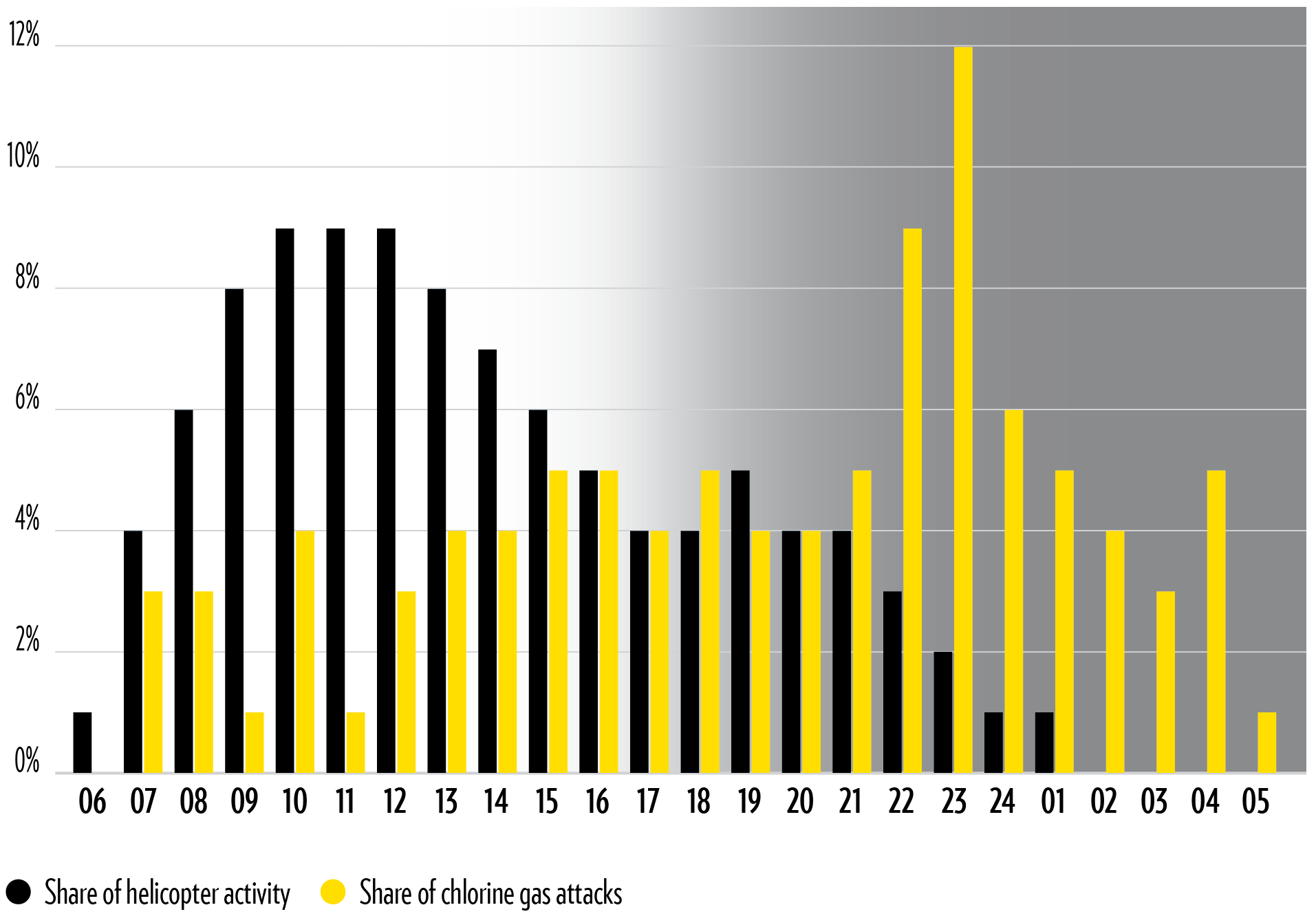

In the case of air-delivered chlorine barrel bombs, we can draw sophisticated conclusions by overlaying chemical weapons attack patterns with the deployment history of Syrian military helicopters as well as loyalist military operations. This task is considerably aided by material attrition of the Syrian air force. Based on open-source information and analysis of satellite imagery, experts from IHS Janes suggest that, as of July 2018, only 10-15 of the 51 Mi-8/17 helicopters on the SyAAF books remained operational. 4

The Tiger Forces: Pattern Attribution

Often described as an elite formation of the Syrian military, the Tigers and their commander, General Suheil Al-Hassan, are commonly credited with pioneering the systematic use of explosive barrel bombs in the early years of the war. In 2017, more than 40 UN member states pointed the finger at Hassan and his air force intelligence associates for coordinating the first chlorine barrel bombing campaign of the conflict in the aftermath of a UN-OPCW investigation into chlorine incidents in Sarmin, Qamenas and Tal Manis in 2014 and 2015.

Since then, waves of conventional and chemical barrels have followed wherever Al-Hassan, or the Tiger, and his fleet of helicopters have gone. The task of tracking their deployments became significantly easier in 2016, when civilian activists set up an integrated system for monitoring Syrian and Russian air operations in the country.

Tracking the Tiger Forces’ Deployment (2016 – 2018)

Tiger Forces Deployment 2016 - 2018

From their home base at Hama Airbase …

… the Tiger Forces deployed to Safira Defense Factories to fight in the Aleppo Offensive in late 2016 …

Aleppo Offensive (2016)

location_on02 November 2016: Khan Alassal, Aleppo

location_on20 November 2016: Al-Sakhour, Aleppo

location_on20 November 2016: Tariq Al-Bab, Aleppo

location_on08 December 2016: Bustan al-Qasr, Aleppo

… and then returned to Hama Airbase to fly attacks in Hama and Idlib province.

Northern Hama Offensive (2017)

location_on25 March 2017: Al Lataminah, Hama

Central Syria Offensive (2017)

In the summer of 2017, the Tiger Forces deployed to Tiyas Airbase and Deir Ez Zor Airbase in central and eastern Syria for the battle against the Islamic State.

Northwestern Syria Campaign (2017-2018)

In September 2017, the Tiger Forces redeployed from central Syria to northern Hama in anticipation of a Russian-led offensive against the rebel-held Northwest pocket. The flight-tracking shows a corresponding Mi-8/17 activity shift from Tiyas Airbase toward Hama Airbase …

… and eventually to the so-called “Vehicle School” forward operating and helicopter base established 20 kilometers northeast of Hama city. This small base accounted for 61 percent of all Mi-8/17 departures in Syria in December 2017.

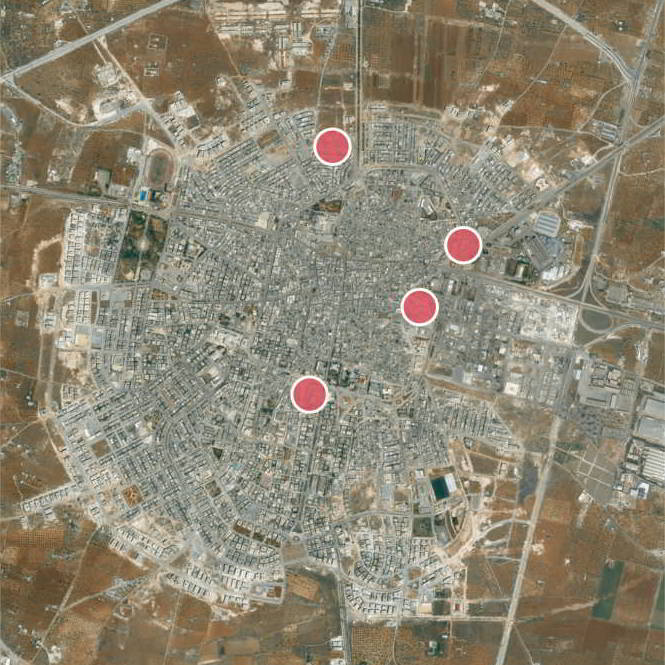

Attack on Saraqib

It is from this base that on 4 February 2018 at 9:02 pm, a Syrian air force helicopter with the call sign “Alpha 253” departed to drop two yellow canister chlorine bombs on the eastern outskirts of the rebel-held town of Saraqib.

location_on4 February 2018: Saraqib, Idlib

Battle of Eastern Ghouta (2018)

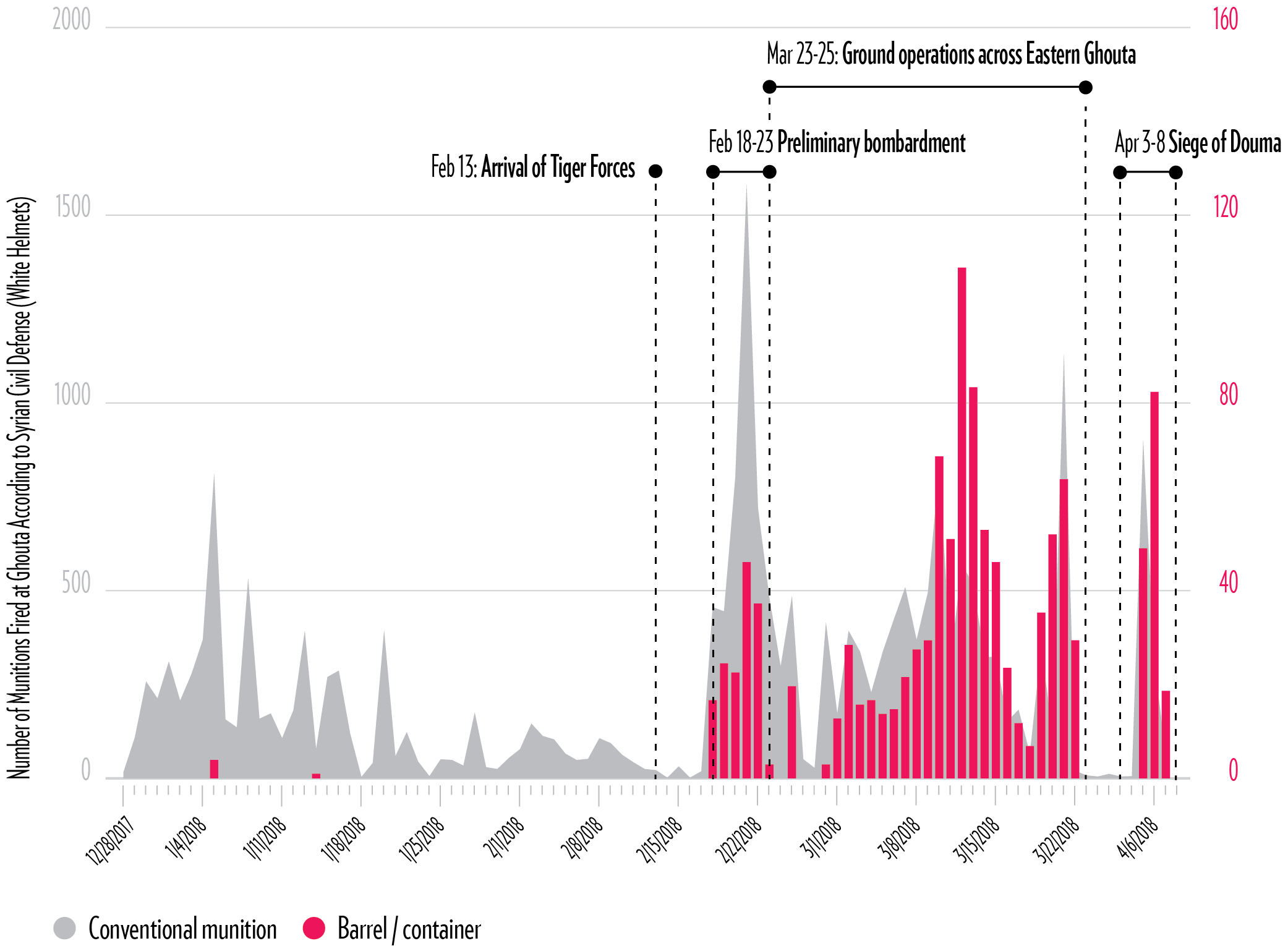

About a week later, on 13 February, the Syrian military announced the redeployment of the Tigers to the Damascus countryside in support of a final campaign to crush the rebel-held pocket in Eastern Ghouta. Again, we can observe the corresponding shift in activity on the air and on the ground.

Beginning on 18 February, Mi-8/17s flying out of the Dumayr Airbase delivered waves of explosive and sometimes chemical barrel bombs throughout the rebel pocket. Local survivors reported that they were stunned and unable to cope with the unprecedented number of indiscriminate munitions.

Barrel Bombs in the Ghouta Campaign (2017–2018)

Attack on Duma

Sector-specific data collected by first responders even allows us to trace the campaign’s incremental advance through the pocket, day after day, town to town, until the final push against Duma.

In this attack, the indiscriminate bombardment culminated in the two notorious chlorine attacks of 7 April, launched from Dumayr Airbase, which involved two yellow canister chlorine bombs.

location_on7 April 2018: Duma, Reef Damascus

Southern Syria Offensive (2018)

In the aftermath of the Battle of Eastern Ghouta, the Tiger Forces moved south to support the Southern Syria Offensive in the summer of 2018 with the helicopters deploying to Khalkhalah Airbase.

The Tiger Forces were neither accused nor targeted during the US-led retribution for the Duma chemical attack. Not until the Turkish intervention in early 2020 did any outside power act to deter the Syrian helicopter fleet.

Chlorine Use in Military Campaigns

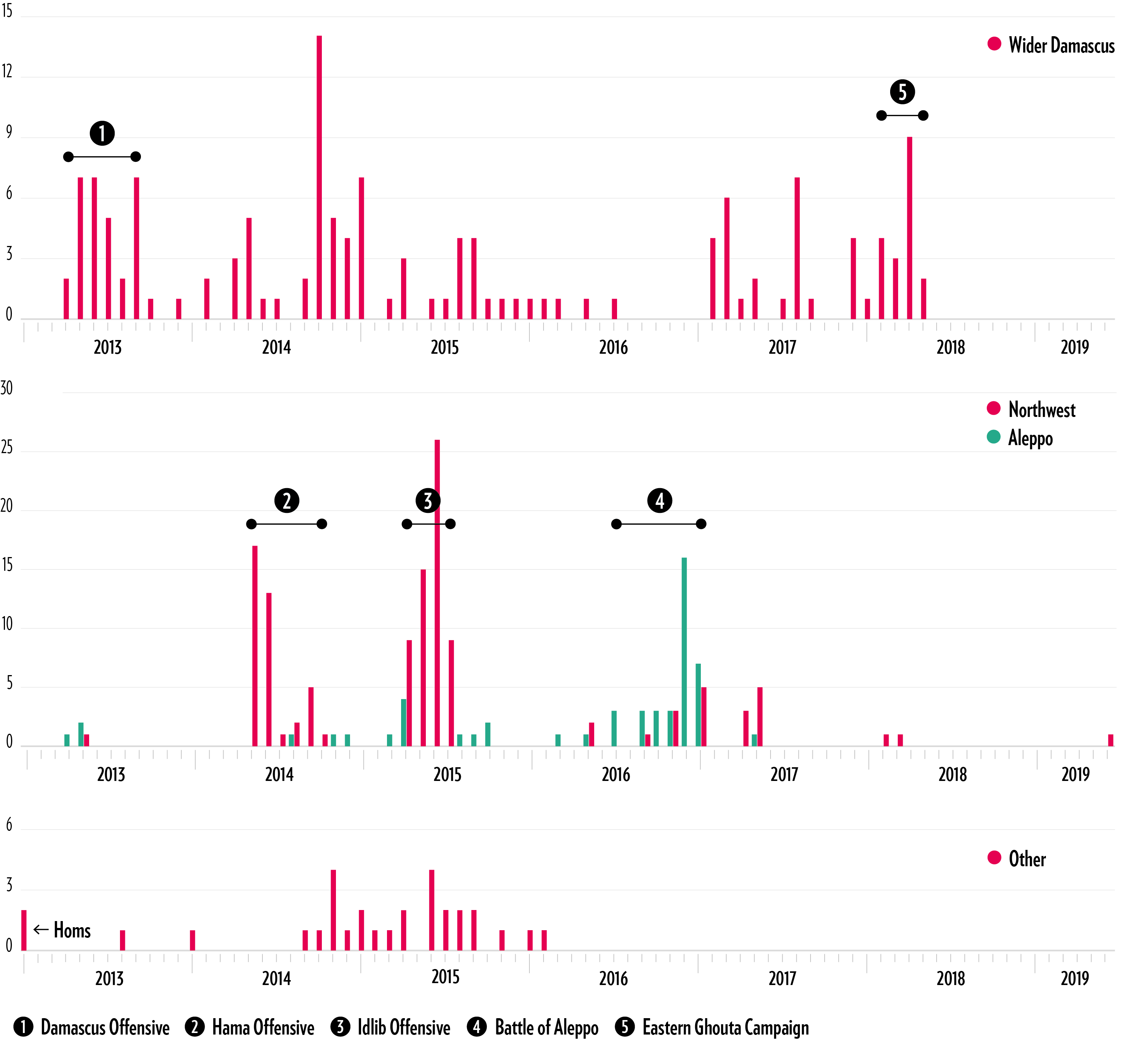

As the Tiger Forces example suggests, we are able to associate significant waves of chemical weapons use with major Syrian government military operations throughout the war. Reviewing our data, spikes in chemical weapons incidents clearly correspond to some of the pivotal battles of the past six years – from their first use in the Siege of Homs in late 2012 to the surrender of Duma in 2018.

Confirmed Incidents of Chemical Weapons Use Over Time (by Region)

We can observe the first major spike of chlorine use as government forces were struggling to repulse a rebel offensive in Hama in the spring of 2014. Subsequently, we are able to distinguish significant peaks for the rebel Idlib Offensive of 2015, the Battle for Aleppo in 2016 and the Eastern Ghouta campaign of 2018. Not visible in the charts but noticeable in the data are individual attacks in support of minor Syrian military operations, such as the loyalists’ defense of Deir Ez Zor in 2015 and its capture of Bayt Jinn in 2016.