Introduction

Even amidst the carnage of the war in Syria, few crimes have riled and vexed the international community as regularly and profoundly as the persistent use of banned chemical weapons. On two occasions, in 2018 and 2019, the United States and its allies, who have otherwise avoided joining the conflict, launched punitive airstrikes against the forces of Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad in retaliation for violations that shook the conscience of the world.

But these were neither the first nor the last chemical weapons attacks recorded in Syria. In two years of painstaking work alongside local and international partners, our team at the Global Public Policy Institute has built what is currently the most comprehensive dataset on reported chemical weapons use in Syria. As of May 2020, and out of 519 reported attacks, we were able to classify 349 as either credibly substantiated, established or comprehensively confirmed. You can explore the information we have collected via our interactive incident map.

Based on our publication from February 2019 (Nowhere to Hide), we not only tally the incidents, but attempt to explain how and why Assad and his military have persisted in the use of such horrific weapons, despite the lingering threat of international retribution. Only once we understand the patterns and logic underpinning the use of chemical weapons in Syria can we appreciate their impact on the unfolding humanitarian disaster and develop more effective policy responses for the future.

The mass of information we collected speaks to the magnitude of the challenge posed by the continuous use of chemical weapons in Syria to international norms. Indeed, our data shows that, despite the occasional calm periods – such as in the aftermath of the 2013 chemical attack near Damascus that sparked an international crisis – chemical weapons have been a mainstay of the Syrian battlefield since late 2012, when activists in Homs governorate first reported suspicious munitions and unexplained symptoms among the local population. These attacks have continued up until May 2019, when Syrian government forces fired chlorine-filled rockets against entrenched rebel positions on a remote frontline near the village of Kbanah in northwestern Syria.

Timeline of the War and Key Events

The Full Picture: Chlorine as a Weapon

In Kbanah, as for most other incidents, the government formation that launched the attack employed domestically designed and produced improvised munitions designs which were filled with chlorine – a non-controlled substance and so-called choking agent with lower lethality than other more notorious chemical agents, such as the nerve agents Sarin or VX, also in the Syrian government’s arsenal. The vast majority of such attacks cause few or no fatalities and thus generally fail to register among the daily carnage of Syria.

But for Syrian government forces, low lethality does not necessarily mean low utility. As a non-controlled substance with legitimate and important civilian applications (e.g., in water purification), chlorine is easy and cheap to procure in significant quantities. Syria’s industrialized infrastructure makes it easy for chlorine to be stored, handled and eventually weaponized without specialized knowledge or equipment. 1

If inhaled, chlorine gas turns into hydrochloric acid which damages the victim’s respiratory system. In extreme cases, victims drown from fluid build-up in their lungs. Medical workers and first responders in opposition-held areas may have counted only 188 direct fatalities as a consequence of chlorine exposure, but have treated over 5,000 individuals who have been injured by the gas, putting heavy strain on already overworked local health services.

I started feeling a dizziness, and my eyes were smarting and I started having a coughing fit. I felt like my chest was filling up. I was about to pass out. There were five nurses at the medical points. We treated ourselves by washing our faces with water and consuming bronchodilators. Medical points recorded no less than 33 injured in the attack, including five medical personnel and 19 women and children. 2

Most importantly, chemical weapons have an outsized psychological effect: heavier than air, chlorine sinks into trenches, bunkers and basements where residents are sheltering from the conventional fighting. Silent and invisible, chemical attacks spread terror among defenseless civilians. Research among survivors of the Iran-Iraq War shows that victims of chemical weapons attacks and their families are significantly more likely to suffer from lifetime post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Heavier than air, chlorine sinks into trenches, basements and shelters.

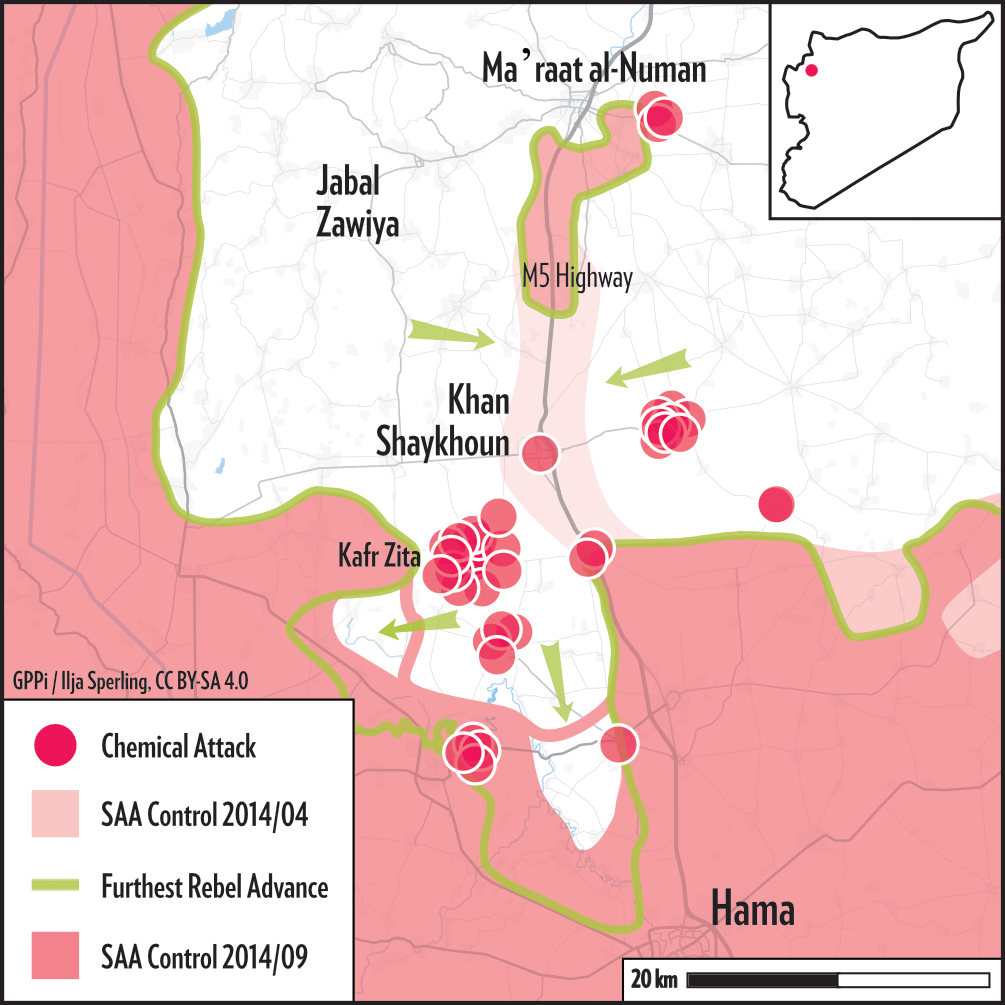

In northern Hama in 2014, a mere 8 months after the fateful “red line” incident of August 2013, the Syrian regime would establish a model that would define its approach to chemical weapons for the following four years – the systematic, widespread, indiscriminate use of chlorine against opposition-held towns.

Hama 2014: The Inflection Point

It is in interviews and testimony collected from witnesses and survivors of chemical attacks that the full extent of their impact – beyond the casualty count – becomes clear. Via our partners or through our own interviews, we have collected many dozens such accounts of victims reliving the dread of anticipation, horror of the moment, and tragic aftermath of these attacks.

Of at least 349 attacks since late 2012, approximately 90 percent occurred after the infamous “red line” incident of August 2013. Our dataset thus speaks to the scale as well as to the gravity of the challenge of chemical weapons use in the conflict. But in order to develop more effective policy responses and advance the drive for accountability, we are looking to better understand how and why the Syrian government persisted, throughout the war, in the deployment of the one set of weapons that carried with it the threat of international retaliation.