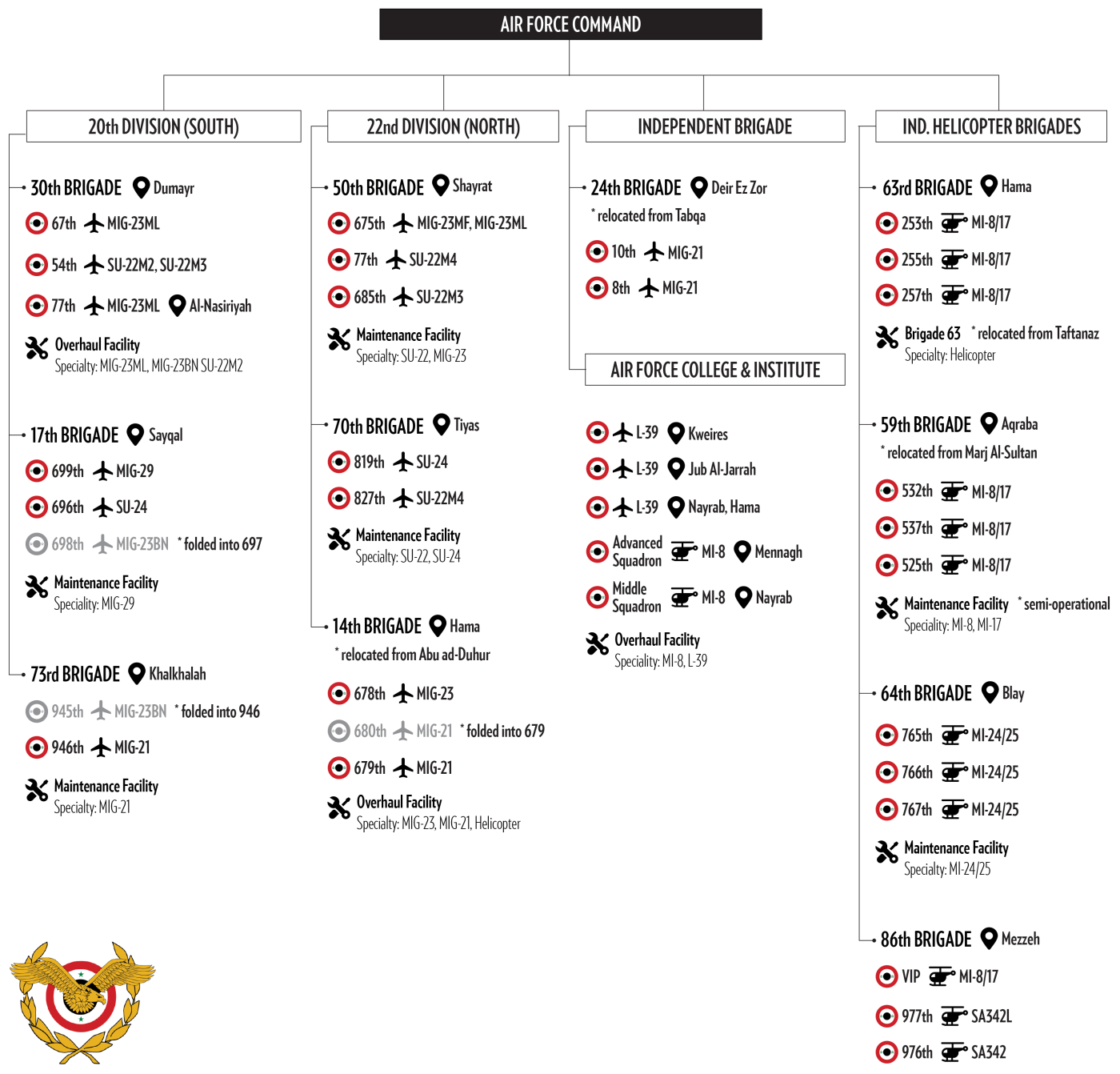

Order of Battle

The SyAAF’s doctrinal order of battle offers a comprehensive overview of the structure and composition of Syria’s remaining active air bases, as well as the evolving makeup of air force divisions, brigades and squadrons over the course of the war. Reconstructing the SyAAF in its current form is essential not only for mitigating its destruction going forward, but also for holding the institution accountable for past crimes. The order of battle provides a useful reference for retracing the functions and positioning of the Syrian air force – and paints a clear picture of its remaining capabilities.

Currently, the SyAAF is made up of two divisions: the 20th Division located at Dumayr Air Base and the 22nd Division based out of Shayrat Air Base. Each division nominally commands one sector of Syria’s airspace and contains three brigades of fighter-bomber and interceptor squadrons. In addition, the SyAAF has four independent helicopter brigades, one of which primarily supports logistics and VIP transports. The Syrian Air Force College and Institute acts as a brigade command and controls two helicopter training squadrons as well as a fleet of L-39 Albatros jets.

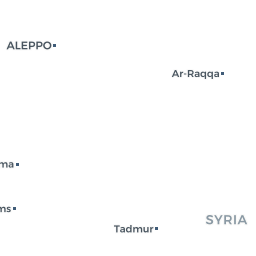

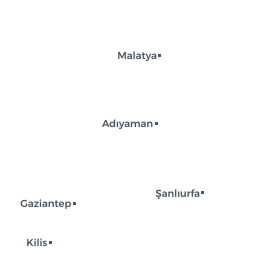

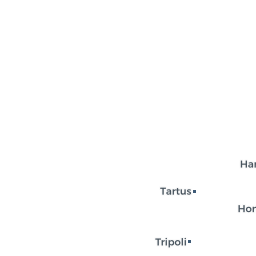

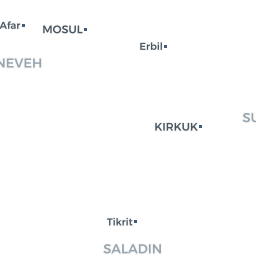

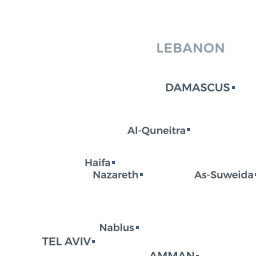

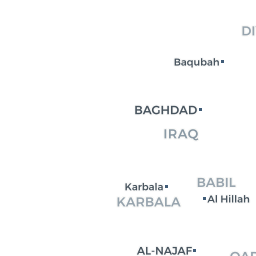

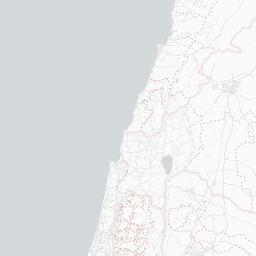

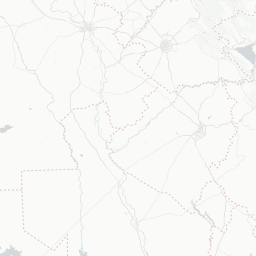

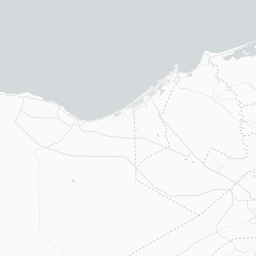

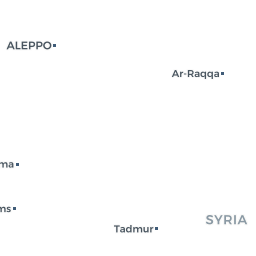

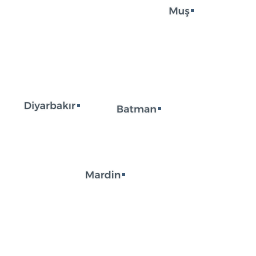

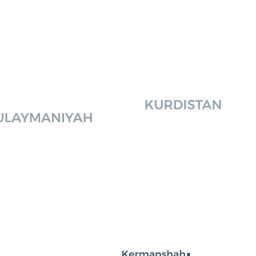

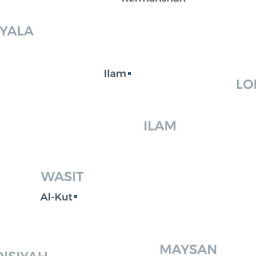

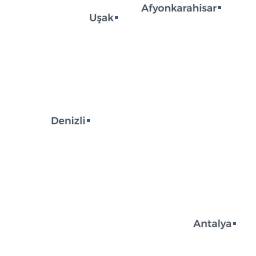

place SyAAF Current Deployments

Over the course of the conflict, the SyAAF lost six of its 17 air bases to insurgents: Taftanaz in January 2013, Jirah in February 2013, Al-Qusayr and Abu ad-Duhur in April 2013, Mennegh in August 2013, and Tabqa in August 2014. These blows, in addition to heavy losses of airframes and pilots, forced the SyAAF to consolidate its existing fleet in a few key locations. While 12 air bases have remained operational throughout the war, most offensive operations have been conducted from a small number of geographically secure bases (mainly Shayrat, Dumayr, Tiyas, Hama, and Blay air bases). The SyAAF also set up eight known forward-operating bases and heliports throughout the country. In addition, seven air bases in Syria have been known to house chemical weapons: Shayrat, Sayqal, Blay, Khalkhalah, Al-Nasiriyah, Tha’lah, and Al-Qusayr air bases.

The SyAAF’s principal maintenance and overhaul facility is based at Aleppo International Airport, and is commonly referred to as the “Factory” or the “Works”. Other large overhaul shops can be found at air bases in Dumayr, Hama and Kweires. In addition, maintenance facilities are present at Sayqal, Khalkhalah, Shayrat, Tiyas, Blay, and Aqraba air bases (although the facility at Aqraba is only semi-operational).

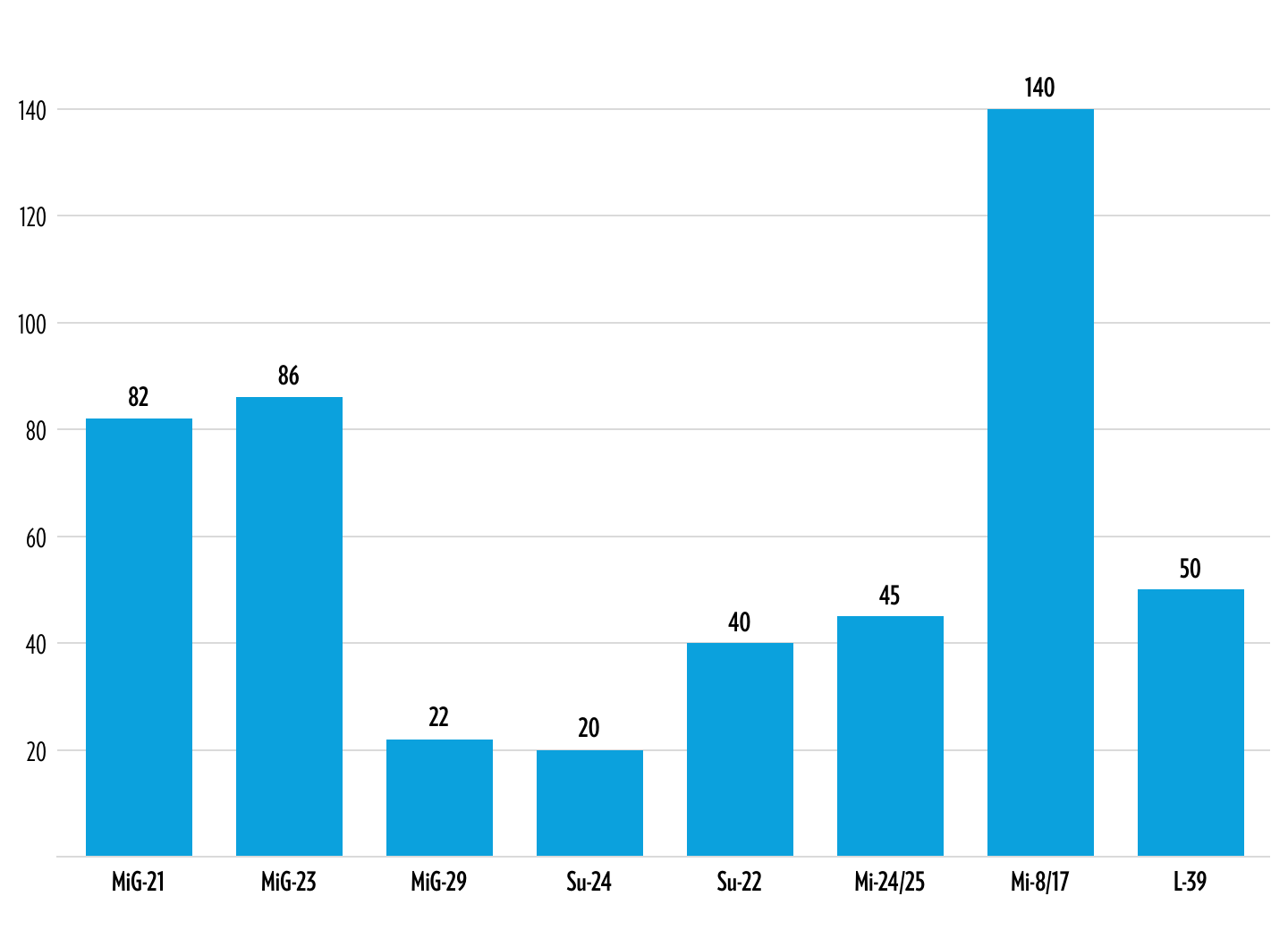

Estimated Number of Airframes in the Syrian Arab Air Force in 2011

Based on our interviews with former pilots and officers, we estimate that the SyAAF possessed 535 airframes at the beginning of the war in 2011. We included in this calculation six fix-wing airframe types and two rotary-wing types. In reconstructing the operability of the SyAAF’s current fixed-wing and rotary fleets, we found that 182 airframes were destroyed in 155 recorded incidents between 2012 and 2020. These losses were individually confirmed through both comprehensive reporting and standard open-source investigations, where possible. Further, we were able to visually identify 157 derelict airframes over the course of the war using the latest satellite imagery available. These obsolete airframes are currently scattered around five air bases across Syria: Dumayr, Hama, Kweires, Blay, and Tiyas air bases.

Our interviews allow us to further estimate that the SyAAF currently has 113 operational airframes (as calculated based on the main airframe types considered). This number has been corroborated through open-source research, from which we were able to identify 61 airframes with individual serial numbers. In addition, while the true number of mission-capable jets and helicopters fluctuates, our estimates are in line with calculations based on sortie rates during major military operations over the past three years. After deducting the airframes that were either lost in combat or rendered obsolete from our 2011 estimate, 113 operational airframes are what remains of Syria’s air force after a decade of war.

Chemical Weapons and the SyAAF

For decades, the SyAAF has served alongside the country’s missile and artillery forces as a key pillar of Syria’s chemical deterrent. While historically aimed at neighboring Israel, the air wing of the Syrian military has repeatedly deployed chemical weapons against insurgents and citizens in opposition-held areas. In our previous report Nowhere to Hide, we found the Syrian government responsible for 98 percent of the 349 recorded attacks using chemical weapons throughout the war. The great majority of these attacks involved improvised munitions, including modified barrel bombs carrying chlorine gas that were delivered via the SyAAF’s Mi-8/17 helicopters. However, in multiple instances, Syria’s air force also used the far more potent and deadly nerve agent Sarin – most notably in a string of attacks in late 2016 and early 2017.

On 29 April 2013, in the first confirmed instance of the SyAAF’s use of chemical weapons during the war, helicopters were observed dropping three small objects encased in what appeared to be cylinder blocks along the outskirts of the opposition-held town of Saraqib. Hitting the ground with a thud rather than an explosion, one of the objects landed in a private backyard, while another crashed into a deserted intersection and a third was recovered fully intact. While reports of chemical attacks had been circulating around the country since late 2012, the international community had possessed no tangible proof until that point. International investigators were able to analyze the third grenade and found that it contained 100 milliliters of Sarin matching the chemical makeup of the Syrian government’s stockpiles. Similar attacks were reported in the following weeks across Northwest Syria. After receiving intelligence concerning the Syrian government’s preparations for chemical attacks the previous summer, the United States had publicly warned the Assad regime that the use of such weapons would be considered a figurative “red line.” When such chemical munitions were again discovered in Saraqib, Western intelligence officials concluded that Syrian government forces had reverted to deploying improvised munitions, this time carrying smaller quantities of chemical agents in an attempt to skirt unwanted attention from the international community.

In October 2013, Syria acceded to the Chemical Weapons Convention and pledged to declare and destroy its stockpile of chemical weapons under international supervision. The move was primarily a way for the Syrian government to avert US intervention following the 23 August attacks on Ghouta, where the Assad regime killed at least 1,400 civilians. Over the following months, Syria declared 27 chemical weapons production facilities (CWPF) across the country, including five underground bunkers and seven hangars located at different air bases. In addition, the Syrian government declared 15 filling structures for chemical bombs, eight of which were housed on moveable trucks. According to recent reporting, every site contained hundreds of gallons of precursors for binary Sarin and other nerve and blistering agents.1 In addition to chemical stockpiles and facilities, the Syrian government declared large numbers of aerial bombs known as M4000 and MYM6000, which were fabricated domestically according to Soviet-era designs and capable of carrying chemical agents. It would take more than three years for international inspectors to secure and confirm the destruction of Syria’s declared chemical agents, munitions and production facilities.

The destruction of the last chemical weapons facility affiliated with the SyAAF – which was located at Sayqal Air Base in rural Damascus – was only certified by the OPCW as dismantled on 6 June 2017, after loyalist forces pushed back Islamic State militants toward the outskirts of the airbase. Satellite images taken between 2014 and 2017 showing demolished aircraft hangars on all seven air bases with declared CWPF further testify to this effort.

Hidden Stockpiles and Surviving Capabilities

However, between 24 March and 7 April 2017 – just a few weeks before the OPCW’s certification of chemical facilities at Sayqal Air Base – the SyAAF delivered at least three separate chemical attacks against opposition-held areas in Northwest Syria. All three missions were completed by a single pilot – a squadron commander from Shayrat Air Base in central Syria. While the first two incidents passed mostly unnoticed by the international community, the third attack killed at least 89 civilians, causing global outrage and triggering punitive airstrikes from the United States. Based on the chemical analysis of biomedical and environmental samples, recovered bomb fragments, intercepted communications from the SyAAF chain of command, and reconstructions of flight paths, international investigators from the OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism and from the OPCW Investigation and Identification Team were able to easily trace the chemical agents and munitions back to the Syrian government’s stockpiles and the responsible jet back to Shayrat Air Base.

According to witness testimonies provided to investigators, Shayrat Air Base housed a second, non-declared chemical weapons facility that was well-secured and hidden underneath two structures in the northwestern corner of the sprawling facility. One witness testified that they had seen government forces loading chemical munitions onto a jet on the morning of an attack. According to reports citing American officials, US targeteers deliberately avoided striking Shayrat Air Base’s second complex for fear of accidentally releasing nerve agents into the air.2 Additional reports suggested an underground storage bunker in Him Shinshar in the rural Homs governorate as another likely chemical weapons storage facility that had escaped disarmament. This underground bunker would be one of three targets of Western airstrikes following the 2018 chemical attack in Duma – suggesting that Western governments had knowledge of the facility and its likely contents.

The Duma incident made clear to the world what foreign intelligence agencies and OPCW inspectors had quietly suspected: Syria had retained parts of its chemical weapons arsenal, as well as the ability to deploy it. And while attributing the attack proved relatively straightforward, establishing the size of the outstanding chemical weapons arsenal and infrastructure has been more challenging. One report by civil society investigators based on defector statements identified a number of likely Syrian Scientific Research Center (SSRC) facilities that appear to have avoided inspection, as well as a number of high-ranking officials who have thus far escaped sanctioning. However, the gradual decrease in defectors from Syria’s weapons program in recent years means that investigators are struggling to produce reliable, up-to-date estimates of stockpiles and facilities. While the OPCW is seeking clarification from Syria on its obviously faulty declarations, the Assad regime has grown increasingly obstinate.

The Chlorine Barrel Bomb Connection

Meanwhile, chemical attacks involving chlorine-filled barrel bombs, which have accounted for more than 90 percent of all chemical bombings during the conflict, have received considerably less international scrutiny. While US and European officials have decried such incidents as clear violations of the Chemical Weapons Convention, they have – except for one unusually deadly occasion – stopped short of declaring the use of chlorine a “red line” that would spark punitive airstrikes. By treating chemical attacks involving chlorine less severely than those involving Sarin, Western actors created a situation in which only one type of chemical weapon faces significant scrutiny and punishment. This asymmetry became evident in the aftermath of the 7 April 2018 attack on Duma, when the United States responded to the chemical attacks involving chlorine by targeting the Syrian government’s nerve agent program and stockpiles rather than the units responsible for the attacks themselves.

The chlorine-filled variations of conventional barrel bombs first appeared in the spring of 2014 – half a year after the fateful “red line” moment following the Ghouta chemical attack and well into Syria’s official disarmament process. At the time, Syrian government forces were fending off rebel advances in the northern Hama governorate. Over the course of three months in the spring of 2015, SyAAF helicopters launched at least 38 chlorine attacks against villages along Syria’s M5 highway. Locals in the small settlement of Kafr Zayta, which was the target of at least 17 attacks, told international investigators that they had stopped counting the number of chlorine bombings. The evidence of chemical weapons was overwhelming: not only had journalists visited the attack sites and smuggled out soil samples, but on the outskirts of town, Kafr Zayta residents had piled high the spent and dented chlorine barrels.

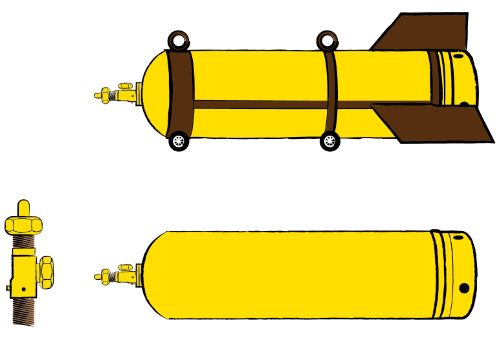

Chlorine Barrel Bombs

According to the OPCW, at least seven distinct types of chlorine-filled barrel bombs have been identified in Syria. In total, our research team has collected data on hundreds of chlorine attacks across nine (out of 14) governorates. The chlorine barrel bomb’s most recent iteration – a yellow canister welded into a metal “cradle” structure with stabilizing fins and wheels – has been in use since at least 2016. Munitions of this specific build have been recovered across four governorates, including in two besieged pockets. In one instance, first responders recovered a dented (but otherwise intact), unexploded chlorine barrel bomb, providing investigators with a reference munition that made it easier for forensic experts to reconstruct shards of burst munitions from later attacks.

According to multiple reports and witness testimony, the production of these chemical munitions occurred at the Zawi factories near Masyaf in the Hama governorate – a production facility under the direct control of Syria’s secretive SSRC weapons programs. Witnesses reported that the so-called Branch 797 was responsible for the development of the chlorine bomb’s design. However, other accounts point toward Branch 797’s previous seat at the Safira Defense factories in southern Aleppo as the original development and production sites. After reviewing satellite imagery of airfields immediately before chemical attacks, investigators now speculate that chemical munitions – at least in their most recent iterations – may be assembled in mobile facilities located at the dispatching air base.

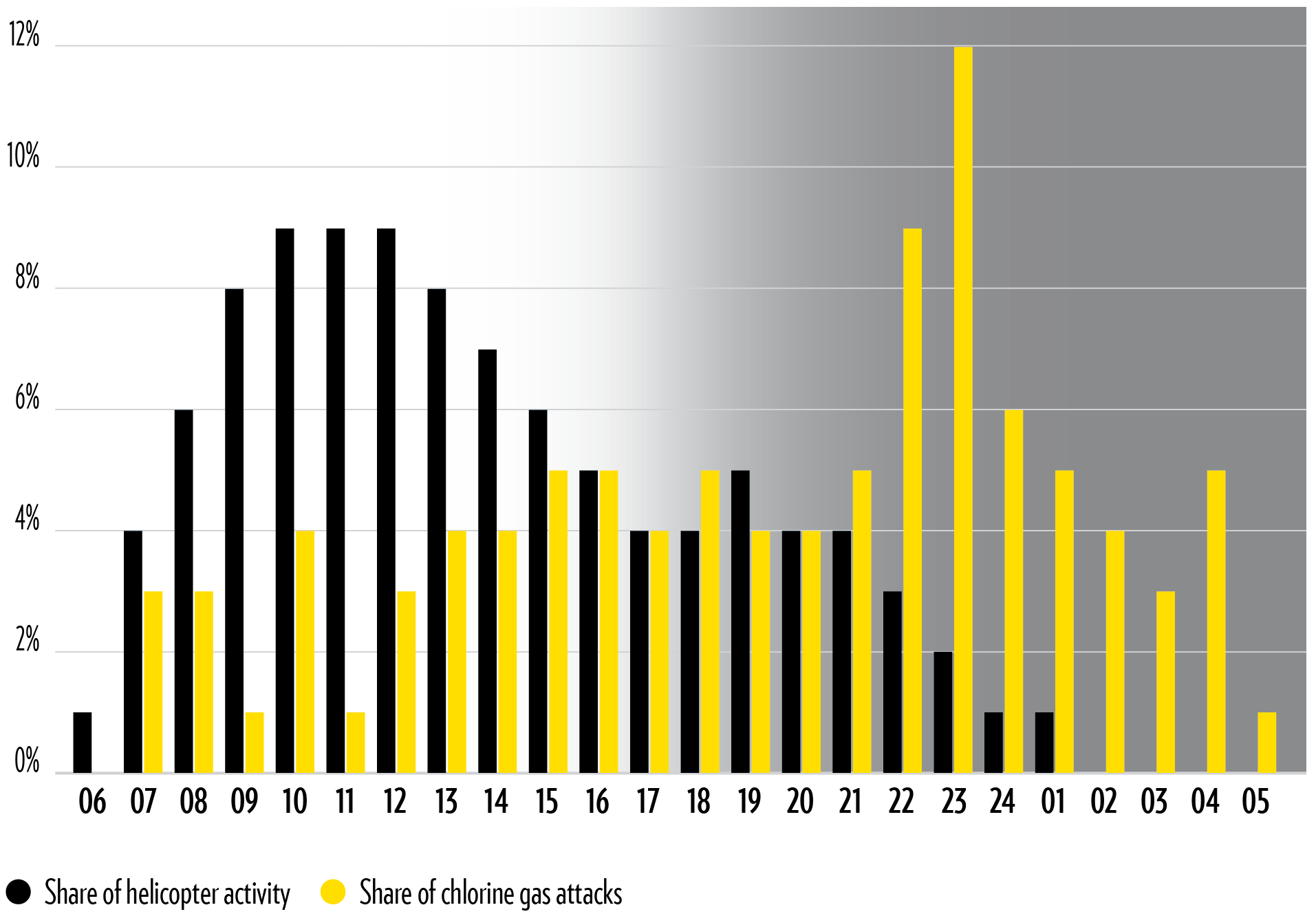

Operationally, the use of chlorine barrel bombs is closely associated with a small formation of six to eight specially configured Mi-8/17 helicopters, formally affiliated with the SyAAF’s 63rd Brigade based at Hama Air Base. However, in practice, this helicopter division is commanded by the so-called “Tiger Forces” (also known as Tigers) under Brigadier General Suhail al-Hassan. Recently rebranded as “Division 25”, the Tigers are commonly credited with pioneering the use of barrel bombs in the early years of the war. In 2017, more than 40 UN member states identified al-Hassan as the commander of the first major chlorine bombing campaigns in 2014 and 2015.3 Flight tracking data, satellite imagery and open-source reporting allow us to trace the Tigers’ helicopter formation from frontline to frontline as they leave in their wake a trail of conventional and chlorine barrel bombs.

Tracing the Tiger Forces Barrel Bombing Squadron

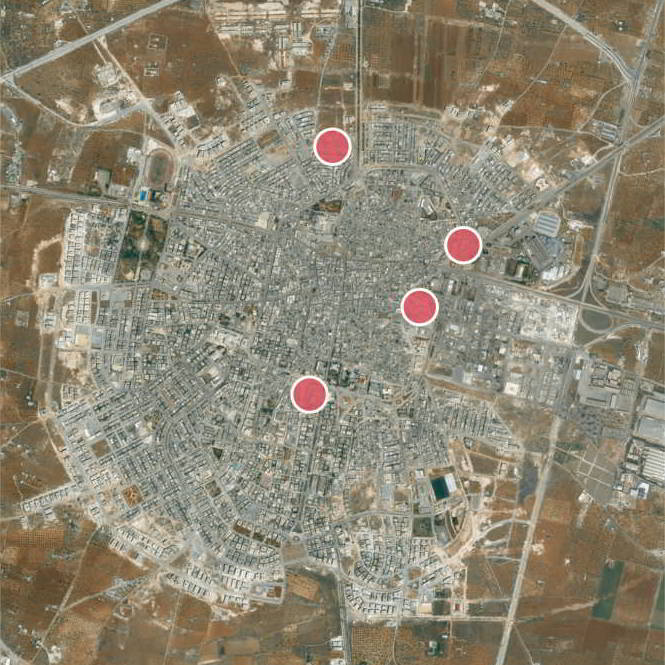

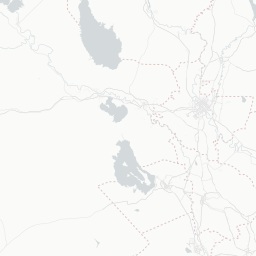

Tiger Forces Deployment 2016 - 2018

From their home base at Hama Airbase …

… the Tiger Forces deployed to Safira Defense Factories to fight in the Aleppo Offensive in late 2016 …

Aleppo Offensive (2016)

location_on02 November 2016: Khan Alassal, Aleppo

location_on20 November 2016: Al-Sakhour, Aleppo

location_on20 November 2016: Tariq Al-Bab, Aleppo

location_on08 December 2016: Bustan al-Qasr, Aleppo

… and then returned to Hama Airbase to fly attacks in Hama and Idlib province.

Northern Hama Offensive (2017)

location_on25 March 2017: Al Lataminah, Hama

Central Syria Offensive (2017)

In the summer of 2017, the Tiger Forces deployed to Tiyas Airbase and Deir Ez Zor Airbase in central and eastern Syria for the battle against the Islamic State.

Northwestern Syria Campaign (2017-2018)

In September 2017, the Tiger Forces redeployed from central Syria to northern Hama in anticipation of a Russian-led offensive against the rebel-held Northwest pocket. The flight-tracking shows a corresponding Mi-8/17 activity shift from Tiyas Airbase toward Hama Airbase …

… and eventually to the so-called “Vehicle School” forward operating and helicopter base established 20 kilometers northeast of Hama city. This small base accounted for 61 percent of all Mi-8/17 departures in Syria in December 2017.

Attack on Saraqib

It is from this base that on 4 February 2018 at 9:02 pm, a Syrian air force helicopter with the call sign “Alpha 253” departed to drop two yellow canister chlorine bombs on the eastern outskirts of the rebel-held town of Saraqib.

location_on4 February 2018: Saraqib, Idlib

Battle of Eastern Ghouta (2018)

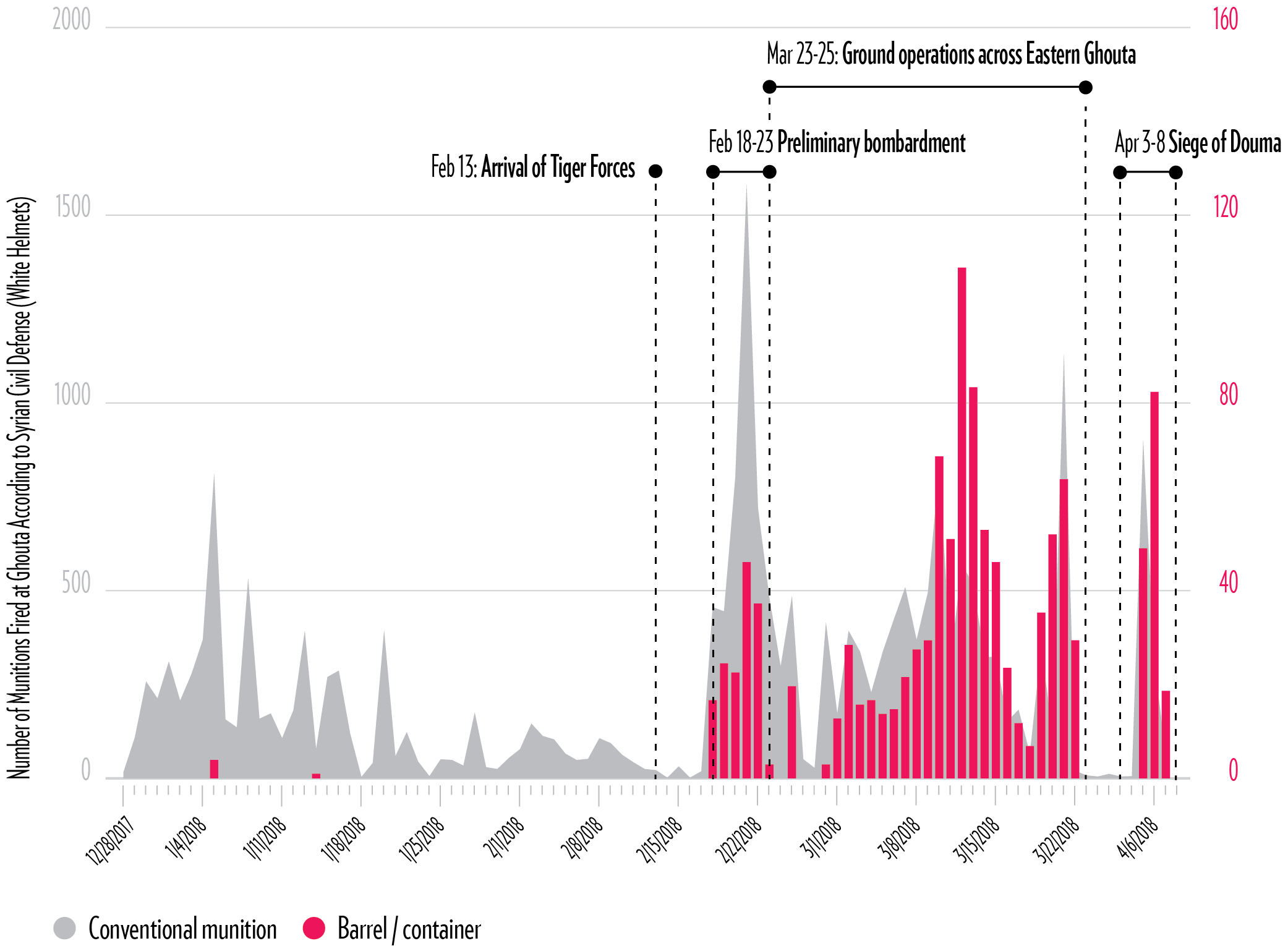

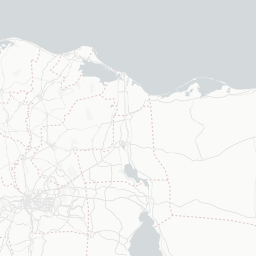

About a week later, on 13 February, the Syrian military announced the redeployment of the Tigers to the Damascus countryside in support of a final campaign to crush the rebel-held pocket in Eastern Ghouta. Again, we can observe the corresponding shift in activity on the air and on the ground.

Beginning on 18 February, Mi-8/17s flying out of the Dumayr Airbase delivered waves of explosive and sometimes chemical barrel bombs throughout the rebel pocket. Local survivors reported that they were stunned and unable to cope with the unprecedented number of indiscriminate munitions.

Barrel Bombs in the Ghouta Campaign (2017–2018)

Attack on Duma

Sector-specific data collected by first responders even allows us to trace the campaign’s incremental advance through the pocket, day after day, town to town, until the final push against Duma.

In this attack, the indiscriminate bombardment culminated in the two notorious chlorine attacks of 7 April, launched from Dumayr Airbase, which involved two yellow canister chlorine bombs.

location_on7 April 2018: Duma, Reef Damascus

Southern Syria Offensive (2018)

In the aftermath of the Battle of Eastern Ghouta, the Tiger Forces moved south to support the Southern Syria Offensive in the summer of 2018 with the helicopters deploying to Khalkhalah Airbase.

The Tiger Forces were neither accused nor targeted during the US-led retribution for the Duma chemical attack. Not until the Turkish intervention in early 2020 did any outside power act to deter the Syrian helicopter fleet.

Command Responsibility

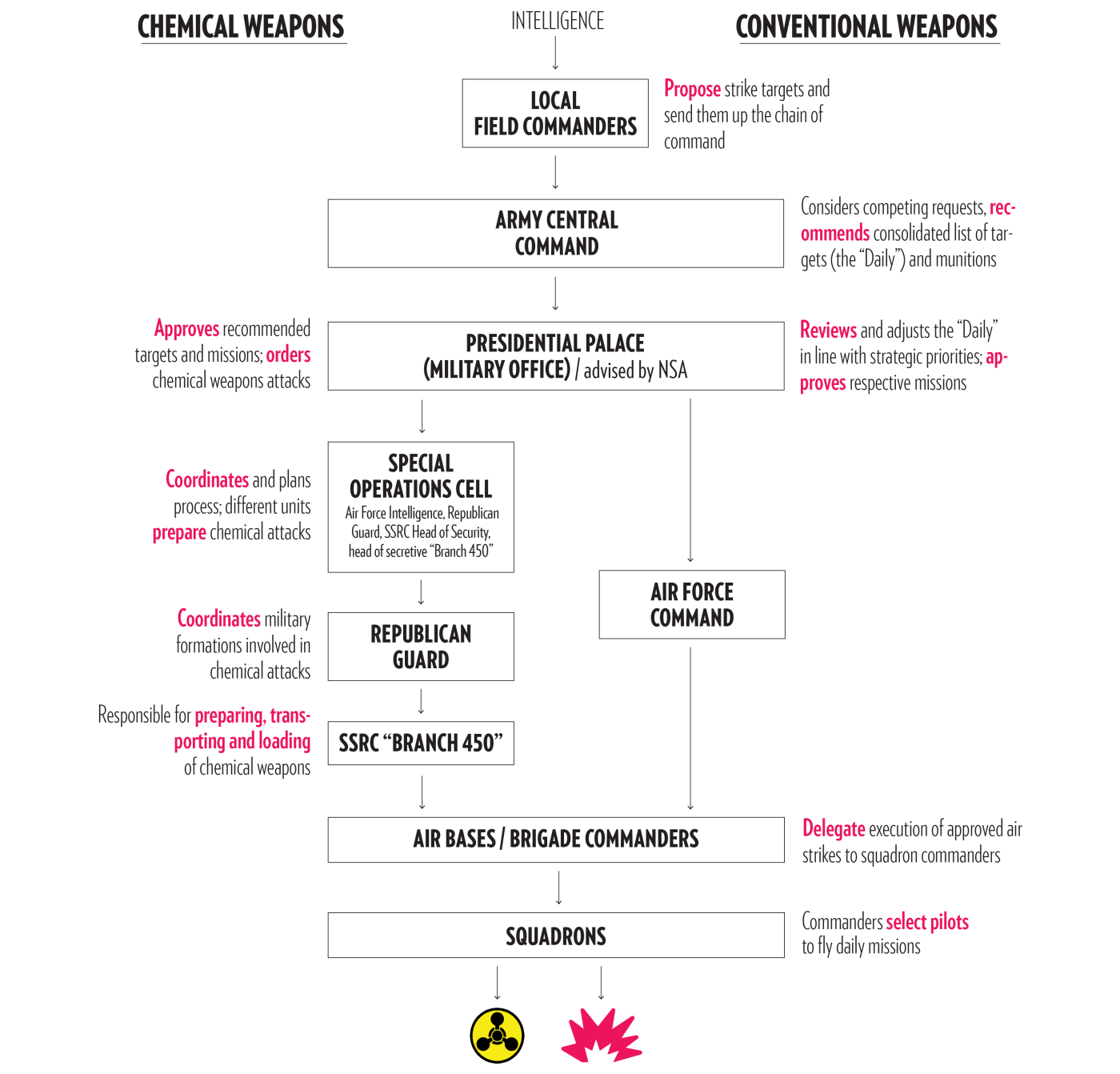

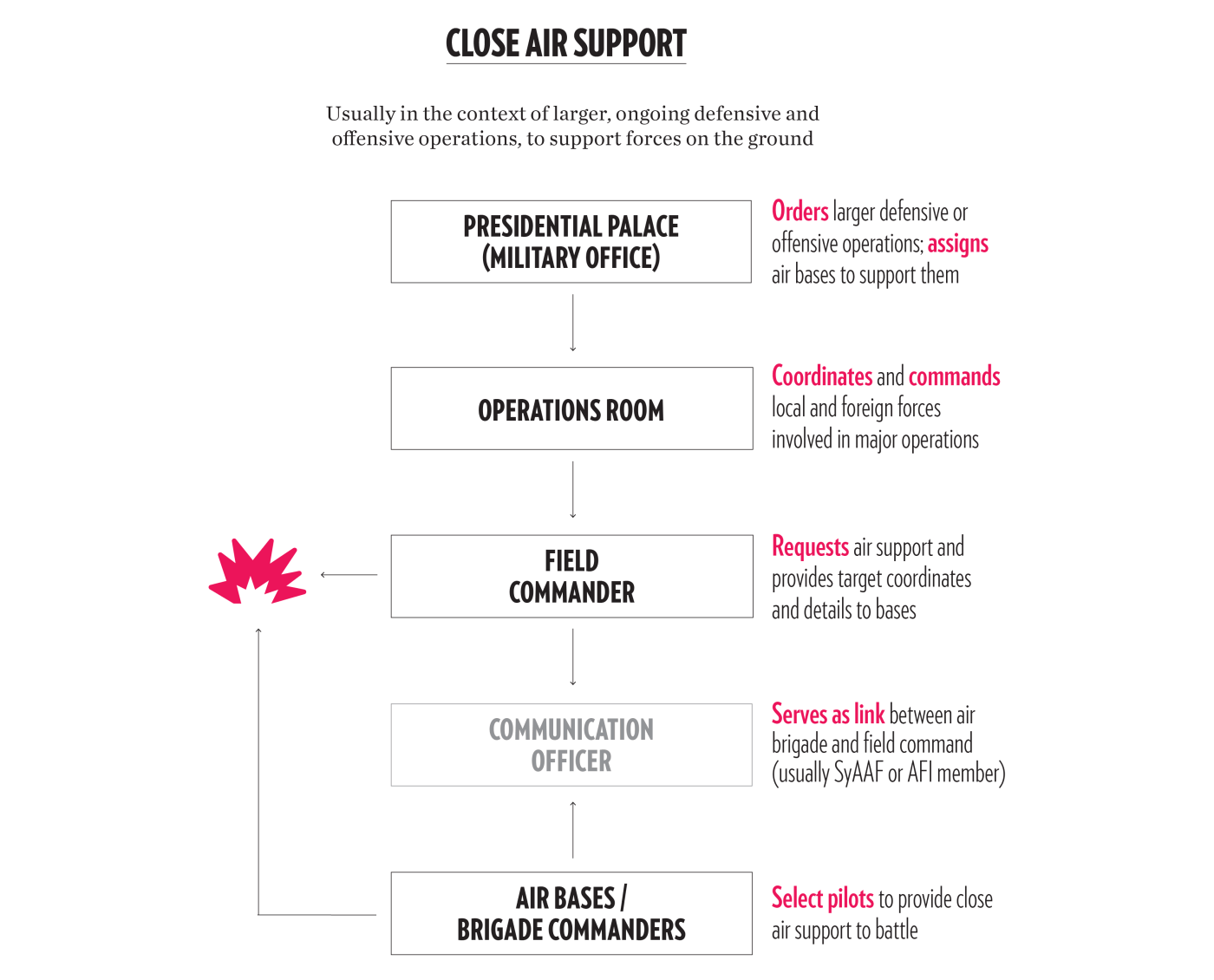

The SyAAF has two regular, distinct processes for generating and approving conventional and chemical air attacks: a deliberate targeting cycle that governs daily, pre-planned sorties, as well as a dynamic targeting cycle for coordinating close air support in battle. The deliberate approach is centrally governed by the highest ranks of Syria’s military establishment. It is highly bureaucratic and covers most of the day-to-day airstrikes conducted by Syria’s air force, as well as the regime’s use of chemical weapons. In contrast, the dynamic targeting cycle involves a more ad-hoc, informal procedure. Understanding how the SyAAF carries out its attacks against civilian populations is an essential part of establishing accountability for war crimes in Syria.

Deliberate Targeting: Conventional Attacks

Most airstrikes conducted by Syria’s air force are the product of a centrally coordinated, deliberate targeting process. Given the scarcity of military resources and the high fuel and materiel costs of air operations, this bureaucratic process allows the Syrian high command to balance competing priorities and resource constraints, while also retaining tight control over the air force - one of its most precious military assets.

Potential targets for the SyAAF are generated on a daily basis using information collected from Syria’s various intelligence agencies. Proposed strike targets and suggested munitions are passed up the chain of command starting with local field commanders. The Syrian Army’s Central Command evaluates the requests submitted by its various military fronts and produces a consolidated list of targets, proposed strike missions and munition types, which it passes along to Syria’s Military Office at the Presidential Palace. Known as the “Daily”, this final list of targets is reviewed by the Syrian president’s closest military advisors, and may be adjusted in accordance with the regime’s current strategic priorities. The approved mission orders are then sent to the SyAAF command, which distributes the instructions to the appropriate brigade commanders. The assigned brigade’s command delegates the orders’ execution to the appropriate squadron commander, who selects a pilot to fly the mission.

The slow pace and heavy bureaucratic process required for the “Daily” precludes targeting mobile enemy units or individuals. Instead, the deliberate targeting cycle typically only designates collective “terrorist hotbeds” – the Syrian military’s designation for communities in opposition-held areas. As such, the deliberate targeting process is less of a clearing house for tactical decisions than a way for the Syrian military’s high command to direct the regular, indiscriminate bombing of opposition-held areas in line with political goals.

Deliberate Targeting: Chemical Attacks

As part of the deliberate targeting process, either the Syrian Army’s Central Command or the Military Office at the Presidential Palace may propose to employ chemical weapons against a selected target. Typically, this choice is made based on the advice of Syria’s Head of National Security and Head of Air Force Intelligence. The decision to use chemical munitions sets into motion a special procedure independent from the targeting process outlined above, and requires high-level coordination between the various branches of the Syrian security state. According to witness testimony, this separate process only governs the use of tightly controlled nerve agents, and not improvised chlorine bombings.

Insider witnesses report that, after receiving orders from the Presidential Palace, a special operations cell is formed under General Bassam Hassan, Syria’s Head of the Presidential Palace Military Office, alongside the Head of Security for the SSRC, the Head of the secretive “Branch 450”, and delegates from Syrian Air Force Intelligence and the Republican Guard. While the Republican Guard – which serves as the regime’s principal praetorian military unit – oversees coordination between various military formations, the actual preparation, transportation and loading of chemical weapons is managed by Branch 450, which is responsible for security at the SSRC and affiliated facilities. Although officially dissolved in 2013, international investigators found that Branch 450 continued operating through at least 2017, when intercepts showed its officers coordinating with Republican Guard leadership in preparation for three chemical attacks in the towns of Al Lataminah and Khan Shaykhun.

Once the order has been passed to the brigade command and the strike missions involving chemical weapons are set into motion, the exact procedures inside the dispatching air bases are largely unknown. While some witnesses suggested that strike orders proceed via the usual chain of command, other interviewees claimed that knowledge about chemical weapons was highly compartmentalized within the air corps. Even brigade and squadron commanders at air bases housing chemical weapons depots reported never receiving instruction on the use of the weapons. However, chemical munition experts agree that to deploy chemical munitions, pilots must first be trained on their use. Air spotters were also able to identify a pattern of specific pre-flight procedures that indicated a chemical weapons payload.

Dynamic Targeting

In the context of large, ongoing operations, the Syrian Army may attempt to shorten the deliberate targeting cycle by requesting close air support for its forces on the ground. At the outset of any major operation, the Syrian Army establishes a special “operations room” tasked with coordinating the disparate local and foreign forces involved in battle. Once approval is granted by Syria’s Military Office at the Presidential Palace, a nearby air base will receive orders to provide air support in the field. A communications officer, either from the SyAAF or the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Services, is then dispatched to provide a direct link between the air brigade and field command. For most established field formations – including the Tiger Forces – these officers are a constant fixture within their ranks.

Once direct communication is established, field commanders can relay their requests for air support to the operations room, where the contact officer on duty passes the target’s coordinates and details on to the commander of the air brigade or their deputy, who will evaluate the request in terms of the availability of airframes, fuel and ammunition before issuing a formal execution order for an airstrike. The air base commander on duty then gives the order to a squadron commander, at which point the latter will choose an available pilot to execute the mission.

In practice, pilots often receive target instructions only after take-off. Since most radio communications between Syrian pilots and commanders are unencrypted, rebel intelligence officers and civilian air observers intercept the bulk of these exchanges. In place of encryption, SyAAF pilots rely on a simple, rotating set of code names for a small number of battles, pilots and munitions, while target locations are relayed using simple GPS coordinates which the pilots enter into commercial map software. This system often gives opposition fighters and civilians the opportunity to anticipate strikes minutes in advance, saving lives and considerably reducing the efficacy of the regime’s targeting process.

Since the dynamic targeting cycle occurs as a result of quick decision-making in the midst of battle, the process regularly breaks down. In some cases, strike coordinates are delayed or changed mid-flight, leading to confusion and inaccurate targeting that can result in failed missions. In rare instances, rebel radio officers – who have developed a detailed understanding of SyAAF codes and procedures – reported being able to impersonate field commanders, broadcasting fake orders and convincing pilots to strike against their own frontlines.

The Impact of SyAAF’s Operations

Assessing the impact of the Syrian air force, both in terms of its military scope and effect on civilians, is essential for understanding its crucial role in Syria’s ongoing war. While the SyAAF has not posed a major threat to rebel operations, its devastating campaigns against civilian populations, cities and infrastructure have shaped the Syrian conflict.

Military Targets

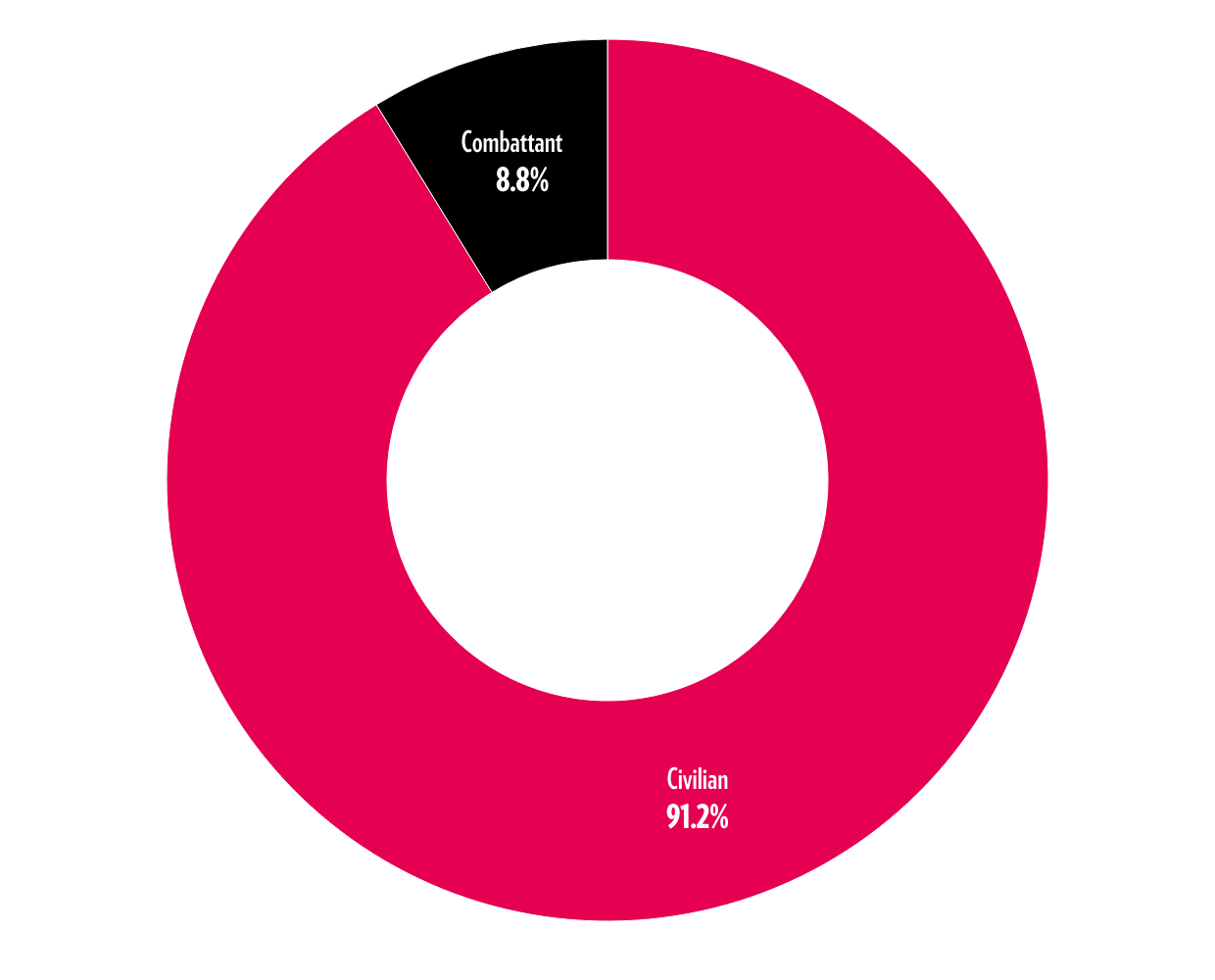

Our interviews with rebel commanders and intelligence officials suggest that Syria’s air force did not play a decisive role on the battlefield prior to Russia’s entry into the conflict in 2015. While the SyAAF had success with rare, intense bombing campaigns that covered broad sections of the frontline, the insurgents we interviewed agreed that the air force’s relatively slow operational tempo, low targeting precision and unencrypted communications meant that its operations posed little threat to early rebel advances. Of the deaths recorded by the Violations Documentation Center over the course of the war, a mere nine percent of fatalities related to air attacks were identified as combatants.

Share of Combatant vs. Non-Combatant Fatalities from SyAAF Airstrikes (2012–2018)

In response to the rare occurrences when the SyAAF successfully concentrated its airstrikes on rebel frontline positions, opposition forces quickly adapted. According to the rebel intelligence officers we interviewed, the prospect of heavy bombardment – which would likely stall the progress of offensive operations – led militant groups to invest more time into operational planning ahead of battles. In such instances, opposition forces often made the decision to advance over terrain that offered more opportunities for shelter and camouflage. In urban environments, rebels heavily invested in constructing tunnels, trenches and makeshift shelters, and established command posts in neighborhoods where buildings contained basements for added shelter. In addition, rebels would often carry out their attacks after dark, as few Syrian pilots were equipped with night-vision equipment.

Most importantly, rebels quickly began tapping into the SyAAF’s radio communications in order to gather intelligence on future airstrikes. Early on, rebel forces were aided in this effort by defected SyAAF pilots and officers, who would train new volunteer spotters on the basics of SyAAF procedures and radio protocols, as well as on practical skills such as map reading. Over the years, these spotters would become highly proficient at deciphering Syrian radio communications. By decoding the precise coordinates of planned airstrikes, opposition fighters could scatter or seek shelter. As a consequence, the rebels we interviewed reported feeling relatively safe from the SyAAF jets and helicopters.

While the SyAAF posed little challenge to rebel operations, opposition officials worried about the impact of airstrikes – particularly barrel bombings – on communities behind the frontlines. In towns across Northwest Syria, near-daily air raids not only caused untold casualties, but also slowly eroded civilian support for continued fighting against government forces. Local leaders reported fearing that the terror resulting from incessant air bombardment was forcing civilians to flee their homes, leading to a loss of opposition legitimacy and incoming tax revenue. There was also concern that a turn in civilian sentiment would put pressure on rebel forces to abandon their offensives, thus undermining the military effort. In this way, it was the SyAAF’s campaign against civilians – rather than their own military losses – that led the opposition to look for ways to down or deter Syrian airframes flying over opposition-held regions. Rebel forces also launched direct offensives against nearby air bases, capturing Taftanaz Air Base on 11 January 2013, followed by Jirah on 12 February, Al-Qusayr on 18 April, Abu ad-Duhur on 30 April, and Mennegh on 6 August.4

Initially, opposition forces had some success in striking at airframes using truck-mounted anti-aircraft cannons that had been captured from government bases, which led to a series of shootdowns during the first months of the air campaign in late 2012 and early 2013. However, these gains were quickly offset when SyAAF pilots began flying at higher altitude. Most of the Syrian air defense materiel that was captured by opposition forces proved derelict or unusable. While rebels implored the international community for more modern weapons, Western officials feared that supplying opposition forces with advanced surface-to-air missiles could lead to their proliferation beyond Syria, and thus threaten civilian air traffic. According to media reports, American officials experimented with modified man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS) that could be tracked or remotely deactivated, but found no workable solution.5

In October and November 2012, Jaish al-Islam managed to capture at least three operational 9K33 Osa – advanced mobile surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems – along with dozens of other missiles from Syrian government forces outside of Damascus. While rarely employed, these advanced anti-aircraft systems proved relatively effective in the hands of the self-taught rebel forces, who used them to down at least four helicopters over the next two years. These SAM systems offered the besieged pocket of opposition territory outside Damascus a means of deterring the SyAAF’s constant attacks.6 In addition, rebel forces were able to capture dozens of HT-16PGJ systems – a North Korean variant of the Soviet 9K310 Igla-1 (SA-16) – from Syrian stockpiles.7 In 2013, Qatar supplied Syrian rebel forces with at least two shipments of Chinese FN-6s (heat-seeking, shoulder-fired missiles). The shipments arrived via Turkey, despite warnings from the US administration that these sophisticated weapons could fall into the wrong hands.

The limited deterrence offered by these anti-aircraft weapons further incentivized SyAAF pilots to target civilians rather than military assets. Now flying at higher altitude to avoid the SAM systems, the Soviet-era jets and “dumb” munitions (i.e., without modern guidance systems) were even less useful in close air support roles against advancing rebel forces. Instead, the SyAAF would direct its firepower against the insurgency’s true center of gravity – the civilian populations residing in opposition-held areas.

Civilian Targets

While the SyAAF may not have left a big impression on the battlefield, it has wreaked havoc on Syria’s civilian populations, cities and infrastructure. As the war progressed and frontlines hardened, Syria’s air force became the government’s principal means of inflicting violence against civilians in opposition-held areas. The Syrian Network for Human Rights has recorded a staggering 59,637 civilian deaths from SyAAF airstrikes over the course of the war, accounting for more than 25 percent of all civilian deaths during the conflict and close to 30 percent of all deaths attributable to the Syrian government forces. The relative significance of these attacks has grown over time as fewer civilians were caught in the crossfires of frontline fighting. In 2016, Syrian and Russian pilots together accounted for 73 percent of all civilian casualties.

Beyond fatalities, thousands more have been left with serious physical or mental wounds as a result of the Syrian government’s air campaigns. The psychological stress of constant bombardment is especially pronounced among children. In the largest and most comprehensive study of children’s mental health in Syria, Save the Children found that almost all children between 5 and 17 years old and 84 percent of adult interviewees suffered from high levels of psychological stress from the fear of bombing.8 According to the researchers, the associated sounds of people shouting or airplanes flying overhead “were enough to trigger extreme levels of fear in children.”9 Two focus group sessions with adolescents had to be abandoned, as the sound of planes left children too scared to continue. Another session broke down after a gust of wind slammed a door shut. In particular, young children described experiencing extreme levels of anxiety which often led to insomnia. Close to half of adult interviewees (48 percent) reported that their children had developed speech impediments or lost the ability to speak entirely.10 At the same time, psychiatric care for internally displaced people in Syria and in neighboring host communities remains almost nonexistent.

In addition to the physical and mental harm, airstrikes have had a severe impact on everyday civilian life in opposition-held areas. Multiple local and international human rights groups have documented what appeared to be deliberate airstrikes targeting civilian infrastructure, including hospitals, schools and camps for internally displaced people. Of the 595 attacks on 350 health facilities since the start of the war, Physicians for Human Rights has attributed more than 90 percent to the Syrian government and its allied forces.11 At least 83 of these attacks involved the use of barrel bombs. In an attempt to protect critical infrastructure such as healthcare facilities, the UN established a deconfliction mechanism in 2014 that identified and recommended no-strike sites to Syria’s conflict parties - up to 778 by late 2018.12 Still, local and international observers registered at least 69 attacks on no-strike sites since Russia’s entry into the war in September 2015.13 An investigation by the New York Times into attacks on hospitals and other humanitarian sites in Syria was able to link the damage of 27 hospitals and clinics from a compiled list of 182 no-strike sites to attacks by Syrian and Russian forces between April and December 2019 alone.14

While it is impossible to neatly disentangle the impacts of wartime violence, all available evidence points toward airstrikes as a main driver behind forced migration during the Syrian conflict. The history of the conflict further suggests strong correlation between escalating air attacks, the intensity of violence in populated areas, and forced displacement. By April 2012, one year after the start of the uprising but three months prior to the onset of airstrikes in populated areas, only 65,000 Syrian refugees had fled to neighboring countries – eight months later, the number of Syrian refugees would climb to more than half a million. In surveys conducted by Handicap International, most Syrian refugees cited the impact of explosive weapons in their home communities as the principal cause of their displacement.15 After years of war, civilian populations came to interpret escalating airstrikes as a precursor for renewed ground attacks. This fear drove many Syrians to seek out the relatively safer areas close to the country’s borders. In 2020, multiple bouts of Russian air attacks against opposition-held areas in Northwest Syria displaced thousands of civilians, despite little change in the war’s frontlines.16

Importantly, the Syrian government’s campaign of indiscriminate bombardment in opposition-held regions has succeeded in creating a psychological and political link between the suffering of civilians and the presence of armed rebels. A representative survey of attitudes among refugees in Turkey showed that Syrians who had lost their homes due to barrel bombings were significantly less likely to support the opposition forces. Instead, they disproportionately chose to renounce armed actors altogether.17 These effects were especially pronounced among women – as anchors of civilian life in Syria, their withdrawal of support can have an outsized impact on the insurgency’s resolve.

To mitigate the threat of airstrikes against civilians, local air observers (known as “watchtowers”) have actively intercepted the SyAAF’s largely unencrypted communications to relay advanced warnings to communities in the path of approaching aircraft. Over the years, these early warning mechanisms have proved essential for protecting civilians from harm.

Starting in 2016, the technology company Hala Systems worked to improve, integrate and automate early warning infrastructure in opposition-held areas. Known as “Sentry” (or “Marsad” in Arabic), Hala’s early warning system collects data on flight take-offs and directions via observers relaying observations from the ground, open-source information and sensors placed in elevated positions throughout the country. The system’s machine-learning algorithm then models potential targets for airstrikes and sends advance warnings to individual subscribers via social media messenger services (Telegram and Facebook). Air raid sirens and warning lights are also installed in Syrian Civil Defense first-response centers, as well as in schools and hospitals. According to Hala, the system has improved to the point that it can warn civilians up to eight minutes before a possible attack, allowing them to disperse or seek shelter in case of an incoming airstrike.

In the absence of a reliable no-fly zone, mitigation measures like the Sentry system offer locals some degree of protection, as well as a mental reprieve from the otherwise constant state of high alert. Comparing casualty data before and after the introduction of the Sentry system, Hala estimates that early warning has reduced the rate of mortality and injury from air attacks in opposition-held areas by 10 to 30 percent, and saved thousands of additional lives in the process.

Conclusion

Through targeted interviews and open-source research, we have been able to trace the development and transformation of the Syrian air force – one of the most powerful and secretive military branches in Syria. By systematically “stacking” the air force and its leadership with Alawite officers and maintaining omnipresent surveillance through the intelligence services, the Assad regime has managed to secure the loyalty of enough Syrian air corps members to sustain SyAAF operations throughout the war, despite the defections of at least 165 pilots and hundreds of other officers.

While largely ineffective against military targets, the SyAAF became the Syrian regime’s primary means of inflicting violence against civilians in opposition-held territory. In addition, the SyAAF has been crucial in enforcing the government’s claim to state sovereignty, even as the Syrian Army lost control of most of the national territory. Since the start of its involvement in the conflict, the SyAAF has consistently targeted civilian populations as part of a broader strategy to depopulate opposition-held territories and delegitimize rebel governance. To drive a wedge between locals and rebels, Syria’s air force developed indiscriminate weapons – including barrel bombs – to associate the presence of opposition militants with constant terror. According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, more than 11,000 civilians died in barrel bombing attacks between 2012 and 2018 alone.

As part of the Syrian regime’s strategy of targeting civilians in opposition-held regions, the SyAAF has consistently deployed chemical weapons against communities throughout the conflict. While most of these chemical attacks have involved chlorine barrel bombs, a series of at least three deadly attacks in the spring of 2017 clearly demonstrated that the Syrian government has retained not only its stockpiles of Sarin, but also the ability to deploy the illicit nerve agent using aerial weapons. The scale of Syria’s surviving chemical weapons program, both in terms of its stockpiles and its infrastructure, remains unclear.

Given the SyAAF’s outsized impact on civilian suffering and displacement throughout the war, we must consider the potential impact that outside military intervention could have had on the Syrian conflict. Our research suggests that, contrary to assessments circulated around 2012 and 2013, the disruption of SyAAF operations would have been militarily feasible and affordable, given the size and vulnerability of the surviving SyAAF fleet. Further, the destruction or grounding of the Syrian air force would have had little direct effect on the war effort, and thus would have posed no immediate threat to the survival of the Syrian state. On the other hand, halting SyAAF operations would have likely saved tens of thousands of lives, alleviated the continued suffering of civilians in opposition-held areas, and prevented the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Syrians.

Outlook

After a decade of war, Syrians are exhausted. The devastation and economic depletion of the country means that armed factions on all sides of the conflict have become increasingly dependent on foreign sponsors. Thus, while the SyAAF remains a looming threat over populations in Northwest Syria, the relative stability of frontlines following the Russian-Turkish agreement in 2020 means that civilians in opposition-held areas are experiencing relative calm for the first time since the start of the conflict. This year, for the first time since 2012, no Syrian civilians in Northwest Syria have died in barrel bomb attacks. Similarly, the continued US presence in Northeast Syria has deterred aggressive attempts by the Syrian government to coerce the local Autonomous Administration of Northeast Syria into submitting to Damascus. Even the Syrian government’s Russian allies are likely to prefer the status quo over the political and diplomatic fallout of rogue SyAAF operations.

While SyAAF mechanics have proved adept at maintaining the remaining airworthy jets and helicopters, the fleet’s medium- and long-term outlook is bleak. At the same time, Syria’s serious balance of payments crisis means that the government will struggle to import sorely needed spare parts and fuel – let alone purchase new equipment – for the foreseeable future. And as the value of the Syrian currency decreases, the salaries of Syrian officers and officials have become insufficient to support their families. In this situation, SyAAF officers are likely to either revert to corruption or abandon their posts to support themselves via second jobs, as occurred in Syria in the 1990s.

Looking forward, Syria’s air force officers and pilots may be even more worried about the prospect of a post-conflict settlement. Considering the air force’s close relationship with the Assad regime and its sectarian composition, opposition officials are likely to insist that the post-conflict government fundamentally rebuild the SyAAF for fear it may be used to threaten them or populations in current opposition-held areas. In addition, given its well-established involvement in war crimes, the SyAAF is likely to be a primary target of future accountability initiatives launched in European and international courts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all our interviewees whose trust, patience and insights made this report possible. We are indebted to our friends and partners at the Open Society Justice Initiative, Syrian Archive, the Syrian Network for Human Rights, the Syrian Civil Defense (“White Helmets”), the Violations Documentation Center, Hala Systems, and many others for their support for this study and the invaluable data they provided.

We would also like to thank Ilja Sperling, who worked tirelessly to bring this report online. In addition, our thanks are due to Amanda Pridmore for her expert editing, and to Katharina Nachbar for steering the overall production process. The opinions expressed in this study and any errors therein are those of the authors.

- play_arrow The SyAAF Today:Order of Battle