Introduction

In the early hours of 7 April 2017, a senior pilot and squadron commander of the Syrian Arab Air Force (SyAAF) prepared to take off from Shayrat Air Base in central Syria. This flight marked his third mission carrying lethal Sarin in just over two weeks. The pilot’s precise routine set off alarm bells for the opposition activists who had tuned into Syria’s radio towers in anticipation of the near daily air-raids:

“Su-22 took off [from Shayrat Air Base], [code-named] Quds 1, known to be the squadron commander. The situation is calm. [This pilot] does not conduct these raids unless he is carrying something dangerous – unless he has toxic materials. The aircraft took off at 6:26.”

A few hours later, at least 89 civilians had been killed in Khan Shaykhun. As images of civilians gasping for air raced around the world, the United States prepared to respond with military force.

Over the course of the war, the Syrian air force has served as the Syrian government’s primary means of inflicting violence and suffering on civilians in opposition-held communities. While the attack on Khan Shaykhun was the war’s most deadly chemical bombing to date, it is far from the only time chemical weapons were deployed by the air wing of the Syrian military, which has served as a principal pillar of Syria’s chemical deterrent for decades. In our research, we have identified at least 336 chemical attacks carried out by Syrian government forces. Only a few of these incidents involved nerve agents such as Sarin – the vast majority involve crude, chlorine-filled barrels dropped from helicopters onto settlements in opposition-held areas.

According to the Violations Documentation Center, at least 34,000 Syrians have perished in air attacks involving conventional munitions, including barrel bombs containing high explosives. Hundreds of thousands more have been injured, driven from their homes and psychologically scarred from the years of near-constant bombardment. As frontlines hardened across the country, the SyAAF grew into the strong arm of the Assad government’s military campaign.

Despite its centrality to the Syrian war effort, the SyAAF has received little public attention or research into its operations, largely owing to its tight internal controls. Our work attempts to shed light on the SyAAF as a military institution at the heart of one of the most devastating and consequential conflicts in the last decades. Our research outlines the Syrian air force’s transformation as a military organization, and offers a thorough account of its current state and operational patterns. Understanding the SyAAF’s structure and protocol is essential for efforts to hold the Syrian government accountable, as well as for drafting effective policy. In no other aspect of the Syrian conflict are so few people responsible for so much destruction.

Methodology Note

This report is based on hundreds of hours of original interviews with current and former Syrian military and security officials. Most notably, the research team debriefed 22 former SyAAF officers and defectors residing both inside and outside of Syria. In addition, we were able to collect information from active-duty Syrian air force personnel by way of interlocutors who served as trusted intermediaries between our research team and the sources, relaying questions and answers. Our team also collaborated with both Syrian and international human rights groups to debrief former members of Syria’s chemical weapons program.

In addition to Syrian military sources, the team interviewed witnesses in opposition-held Syria, including opposition militants and officials who were involved in tracking, mitigating and responding to Syrian air force attacks in areas outside of government control. These key witnesses included twelve rebel intelligence officers and four air observers (also called “watchtowers”). We also interviewed opposition-affiliated civilian officials as well as first responders from the Syrian Civil Defense (i.e., “White Helmets”), Syrian medical personnel working with local health services on the ground, local and international civil society representatives involved in collecting data on violations, and civilian victims of air attacks.

Given the sensitivity of the subject matter and the potential risks for the defectors, their relatives inside Syria, and to our partners involved in accountability efforts, we made the decision to keep the identities of our interview partners confidential. Unless otherwise specified, all information included in this report drawn from interviews has been independently corroborated by at least two sources with direct knowledge of a given subject (as well as, where possible, open-source documentation and reporting).

Using interviews, open-source information and satellite imagery, the research team also compiled multiple large datasets covering SyAAF facilities, equipment, deployments, and personnel. In total, the team identified 165 SyAAF pilots who defected from the organization over the course of the conflict. We have also confirmed the deaths of 201 pilots over the course of the war, 144 of which were individually identified and connected to airframe losses. In total, the team confirmed 187 aircraft losses in 155 separate incidents, as well as 157 airframes that were discarded across various air bases since the beginning of the war.

To determine the current number of airworthy jets and helicopters, the research team corroborated information obtained in interviews with open-source research and satellite imagery. Using this combined method, we were able to identify at least 61 numbered airframes in airworthy condition. To calculate this total, we subtracted the confirmed airframe losses and discarded airframes from our estimate of 535 airworthy airframes at the beginning of the war, which we derived from our interviews. Finally, the research team utilized detailed air observation data concerning daily flight activity across the country, which was collected via sensors as well as individual records from air observers, to corroborate the numbers.

Over the course of this project, we have relied on our Syrian partners, including the Syrian Network for Human Rights, the Violations Documentation Center and the Syrian Civil Defense, for detailed records on civilian casualties during the conflict. Both the Syrian Network for Human Rights and the Violations Documentation Center follow established methodologies for confirming individual incidents, and further corroborate the identities of all attack victims with direct witnesses or family members. The Syrian Civil Defense also maintains detailed records of air attacks in opposition-held regions.

The History of the Syrian Air Force

Founded in 1946 after France’s withdrawal from Syria at the end of World War II and the resulting Syrian independence, Syria’s air force evolved from its early years as a symbol of national progress, modernization and optimism into a pillar of regime repression. In a country with a long history of military coups and factionalism, the history of Syria’s air branch is inextricably intertwined with that of the Syrian state, the Baath party and the regime built by Hafez al-Assad, who was himself an air force pilot. Understanding the relationship between Syria’s military branches and political leadership is essential for recognizing the role of the SyAAF in maintaining the current regime.

The Beginnings (1946–1972)

Established in 1946 in the wake of France’s withdrawal from Syria following the Damascus Crisis,1 the early Syrian Air Force (SAF) was a symbol of the newly independent country’s sovereignty and ambition. The nascent force was briefly trained by French pilots before the Syrian government hired a small cadre of Croatian, German and British pilots.2 In 1948, the air wing of Syria’s military saw its first action in the Arab-Israeli War, in which it lost four airframes out of its 38 operational aircraft.3 Over the next decade, successive Syrian governments invested significant resources into expanding the SAF, purchasing new airframes from the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Czechoslovakia. To bolster the growing program, pilot recruits and personnel received training in Egypt, Iraq, the United Kingdom, Italy, Czechoslovakia, and Poland.4

An estimated 123 pilots graduated from Syria’s flight school between 1947 and 1958, at which point the SAF folded into the Egyptian Air Force under the newly formed political union, the United Arab Republic (UAR). Most of these new recruits were Sunnis, Druze and Christians from educated backgrounds, with only a few Alawites among the early promotions.5 In 1950, future leader Hafez al-Assad entered the Homs Military Academy. This period also marked the beginning of the country’s military cooperation with the Soviet Union – in 1956, Syria received 25 MiG-15 aircraft from Moscow in a bid to counterbalance growing Israeli capabilities.6

Between Revolt and Regime (1973–1990)

Following the dissolution of the UAR, Egypt retained most of Syria’s air force equipment, forcing Damascus to rebuild its air force from scratch. Following the 1961 coup d’état in Syria that restored the Syrian Republic and brought the Baath party into power in 1963, the air branch was reintroduced as the “Syrian Arab Air Force” (SyAAF) – a name it has kept to this day. As commander of the SyAAF (and later, President of Syria), Hafez al-Assad worked to turn Syria’s air force into his own power base and a regime stronghold in the new Baathist state.7 To accomplish this goal, al-Assad developed a powerful and independent Syrian Air Force Intelligence Service, which slowly grew to supervise the other intelligence services in Syria, and gradually cultivated an Alawite majority within the air force.8

Soviet assistance was an essential part of the institutional and material reconstruction of Syria’s air branch. While al-Assad attempted to diplomatically keep Moscow at arm’s length throughout the 1970s, the Soviet Union delivered close to 100 MiG-21 jets to the SyAAF9 in the lead up to the October (or Yom Kippur) War of 1973. During this time, SyAAF MiG-21 pilots received advanced training in air-to-air combat from Soviet forces.10 From 1968 to 1973, large numbers of Syrian MiG-15 and MiG-17F aircraft were sent to the LZR-2 Works in Poland for extensive overhaul. Despite these investments, the SyAAF suffered heavy aircraft and personnel losses in its aerial engagements with Israeli warplanes during the October War. After the war’s conclusion in 1973, the SyAAF had access to 338 combat aircraft, including up to 200 MiG-21s, 80 MiG-17s and 80 Su-7s.11

However, the violent uprising of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood between 1976 and 1982 was a turning point for both the Baathist regime and Syria’s air force. As the al-Assad government moved to crush the rebellion, the military establishment and SyAAF faced internal divisions. Multiple pilots defected with their jets to the neighboring countries of Iraq and Jordan. In late 1981, as the Muslim Brotherhood rebellion was reaching its climax, a car bomb killed General Mamdouh Hamdi Abaza, the commander of the SyAAF. A few months later, in early January 1982, the al-Assad regime discovered an elaborate conspiracy inside the military involving plans for SyAAF airstrikes at key loyalist positions in and around Damascus.12 The plot, which was led by Major Fawzi al-Azzawi from Deir Ezzor,13 was betrayed and hundreds of mostly mid-ranking officers were immediately purged and executed.

Only a few weeks later, the Baath regime faced further damage when multiple Sunni air force officers and pilots refused orders to strike at the central Syrian city of Hama. At that time, Hama was in open revolt against the Syrian government, battling loyalist forces under the command of President al-Assad’s brother, Rifaat al-Assad. As a result of this disobedience, dozens of officers and recruits were arrested or expelled from service. On 9 June 1982, the Israeli invasion of Lebanon provided the Baath regime with the opportunity to rid themselves of dozens of officers whose loyalties had come into question. In the span of mere hours, Israel downed at least 82 Syrian jets.14 Insider witnesses claimed that the true count of destroyed airframes was higher than reported. They remembered a growing sense of dread among the Sunni officer corps, as more than 70 pilots were sent to their deaths at the hands of the vastly superior Israeli forces.

In the immediate aftermath of the 1982 Lebanon War, purges inside the SyAAF pilot and officer corps intensified at the same time that special recruitment drives increased the number of Alawites within the officers’ corps. Sunni officers recalled Alawites making up 80 to 85 percent of all new military academy recruits among cohorts from the early 1980s.15 While the transformation was gradual given the years of training required to produce capable pilots, the shift was unmistakable: One Sunni officer, who started his career in the early 1980s serving alongside only one or two Alawite colleagues, returned to the same base years later to command a squadron composed entirely of Alawite pilots from the ruling family’s sect.

During this period, the Soviet Union rapidly increased its deliveries to Syria, which had become one of its largest buyers of military equipment. Between 1982 and 1986, the SyAAF added around 40 MiG-23ML and 20 MiG-25PDS jets to its arsenal, as well as close to 100 Su-22M-3 and Su-22M-4K (Fitter) aircrafts.16 However, Syria struggled to pay its debts to Moscow (which surpassed $17 billion USD), and thus received only 24 of the 48 MiG-29s and 20 of the 24 Su-24MKs that it ordered in 1986.17 These were the last new combat aircraft to enter Syrian service to date – a prelude to the total halt on military aid to Syria after the Soviet Union’s fall.

Structural Decline (1990–2010)

The collapse of the Soviet Union led to a massive fiscal and economic decline across Syria, forcing the government to tighten its belt and reduce military spending. Given the shortages of spare parts and fuel, which the government struggled to import due to its lack of foreign currency and maintenance capabilities, the SyAAF was large on paper, but remained all but grounded for most of the following two decades: average flight hours decreased from 12 hours per month to no more than 90 minutes. Meanwhile, once proud military pilots were forced to take on civilian jobs, including as cab drivers, in their now ample spare time.18 While many junior officers drove taxis, senior commanders often subsidized their salaries through corruption. All subsequent attempts at Russian aircraft and arms sales failed, even after Russia announced that it would forgive most of Syria’s debt in January 2005.19 By 2007, Syria possessed a much larger air force than it could hope to maintain or modernize. Of its 584 combat aircraft, most were obsolete models. Similarly, its training practices and doctrines had not been updated in multiple decades.20

The aftermath of the 2005 Cedar Revolution and the 2006 Lebanon War pushed Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, who had succeeded his father in 2000, to deepen his country’s strategic alliance with Iran. The ratification of the joint Strategic Defense Cooperation Agreement between the two states in November 2005 led to the establishment of two Iranian-Syrian signals intelligence stations in the Al-Jazeera region of northern Syria and in the Golan Heights.21 In addition, Iranian advisors joined the missile and avionics sections of Syria’s secretive weapons programs. With Iran’s financial support, Syria was able to purchase 33 second-hand MiG-23 jets and shipments of spare parts from Belarus, which it used to produce two dozen “new” aircraft at the “Factory” – i.e., the SyAAF’s main overhaul and maintenance facility in Aleppo.22 The Syrian government increased flight hours and contracted the 150 Aircraft Repair Plant in Kaliningrad to overhaul 36 Mi-25 helicopter gunships, of which 24 were returned to Syria before March 2011.23 Between 2010 and 2013, the 514 ARZ Aircraft Repair Plant in Rzhev, Russia upgraded most of Syria’s fleet of Su-24 jets to M2 standard.24 In addition, in 2009, the Russian Aircraft Corporation MiG aided the SyAAF in transitioning to a more modern maintenance system.25

According to our interviews with former air force pilots and officers, on the eve of the 2011 uprising in Syria, the SyAAF had an estimated 535 airframes on the books – only a fraction of which were combat-ready. Despite the air force’s structural decline in the decades preceding the uprising, the political and social transformation of the SyAAF into an Alawite-majority force – a process in which the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Services played a significant part – ensured that Syria’s air branch would be a key player for the Baathist government as it faced the popular uprising.

In Revolution and War

In Revolution and War

The uprising that swept Syria in the spring of 2011 put the Syrian air force in a precarious position. Faced with protests that reminded the Syrian regime of the bloody 1980s, the reconfigured SyAAF was among the last military branches to actively suppress the uprising. As pilots were instructed to fly against their home communities, the cohesion of the carefully rebuilt air corps was put under immense strain. And after decades of neglect, the aircraft themselves were in no shape for active combat.

Loyalty and Revolution (2011–2012)

As large crowds of protestors gathered across Syria in the spring of 2011, the country’s once ubiquitous military and intelligence apparatus faced an uphill battle. Within days of the initial uprising, the core Syrian regime assembled what became known as the Central Crisis Management Cell – a nightly roundtable of the country’s most prominent Baath party officials and security chiefs to coordinate the crackdown on protests and activists.26 As the demonstrations spread across the country, the Syrian government’s grip on control began to slip. As early as April 2011, reports circulated of military units refusing to fire on civilians, and instead choosing to defect. Throughout the country, dissident military officers severed ties with the Syrian government, culminating in the formation of the Free Syrian Army on 29 July 2011. Over the next year, defections accelerated across all ranks, from high-level officials to ordinary conscripts – while some of these soldiers joined the insurgency, many thousands more simply abandoned their posts.

According to our sources who were active in the SyAAF at that time, a similar struggle took place among air force officers and pilots. Starting in early 2011, those suspected of disloyalty were subjected to intense questioning and surveillance by Syria’s notorious Air Force Intelligence Services, as well as by their own colleagues. SyAAF members who defected after the start of the uprising reported a general cloud of suspicion hanging over the Sunni officers in particular. At the same time, the SyAAF’s Information and Indoctrination Unit began an internal campaign of propaganda, attempting to portray the uprising as the work of terrorists and foreign conspirators. According to the defectors, air force officers and pilots were shown videos of prisoners giving seemingly forced confessions, detailing conspiracies and threats against Syria in general and the SyAAF in particular.

Internal divisions quickly formed along sectarian lines as Sunni officers and pilots reported being sidelined and put under special scrutiny at the hands of the Alawite-majority Syrian Air Force Intelligence Services. Even high-ranking Sunni officers reported living in fear of denunciation by their Alawite subordinates and deputies, who were commonly suspected of working as informants for different intelligence services. One high-ranking defector described how Sunni officers came to view summons to the Syrian Air Force Intelligence’s regional headquarters as essentially arrest orders. The interviewee estimated around 20 pilots – all Sunni – disappeared in the first months of the uprising. Ultimately, the campaign of intimidation against internal opposition and even moderates culminated in the assassination of Major General Abdullah al-Khalidi of the SyAAF command in Damascus in October 2012. According to multiple media reports as well as sources close to him, al-Khalidi opposed the bombing of Syrian cities and had considered defecting to the opposition.

As tensions inside the SyAAF grew, the security services began tightening restrictions, particularly on Sunni pilots: flying time was cancelled or strictly reduced out of fear of defection or friendly fire, and vacation requests were categorically denied. In addition, movement beyond air base perimeters and military housing complexes was strictly curtailed, and the surveillance of pilots and their families increased. Pilots from areas in open revolt were frequently called in for interrogation – the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Services monitored the contents of their phones and laptops, and would often ask them to provide details on revolutionary figures who might be their extended family members or neighbors. As a consequence, pilots felt particularly disconnected from ongoing events and under constant surveillance – both from their own intelligence services who questioned their loyalty and from the surrounding communities.

Joining the Fray (2012–2013)

Early in the conflict, even as the government was losing control of entire swaths of territory, the Syrian military’s high command seemed reluctant to engage the SyAAF in any missions beyond support functions, which included the transport of security personnel to revolting cities in early 2011. While occasional reports of helicopter gunships striking defecting army units emerged throughout 2011,27 the Syrian regime appeared to restrain its air wing, potentially to avoid drawing unnecessary ire from Western states whose intervention in the Libyan conflict had led to the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi.

After multiple failed attempts to de-escalate the situation, the conflict in Syria erupted in the summer of 2012 when a UN-brokered ceasefire collapsed after news spread of a horrific sectarian massacre at the hands of government forces in the town of Houla. On 4 June 2012, President Bashar al-Assad spoke defiantly before the Syrian Parliament, vowing to “cure the homeland” of “terrorism.” In his speech, he explicitly alluded to the government’s crushing of the Muslim Brotherhood uprising from 1976 to 1982.28 However, even as Assad spoke, rebel forces were surging across the country. Over the following weeks, opposition fighters captured the strategic towns of Al-Qusayr and Saraqib, and advanced on the country’s largest city, Aleppo, as well as on the capital, Damascus.

While the research team has yet to uncover a formal order for the SyAAF to join the battle, media reporting and civilian casualty records show that from mid-July 2012, individual reports of air strikes against both rebels and civilian targets began to mount as rebel forces moved to seize eastern Aleppo and the outskirts of Damascus. On 18 July – the same day that a bomb ripped through a meeting of senior Syrian security officials in downtown Damascus – the SyAAF committed its first massacre on the outskirts of the capital, killing at least 100 mourners taking part in a funeral procession in Sayyeda Zeinab.29 By the end of the month, jets were regularly observed flying close air support missions alongside government forces in and around Aleppo. By mid-August 2012, reports emerged from multiple cities across central and northern Syria that government helicopters were unloading explosive-filled improvised munitions, soon to be known as “barrel bombs,” in populated areas.30

Defections From SyAAF (in Persons), Air Frame Losses (in Number of Air Frames), and Civilian Casualties in 2012 and 2013

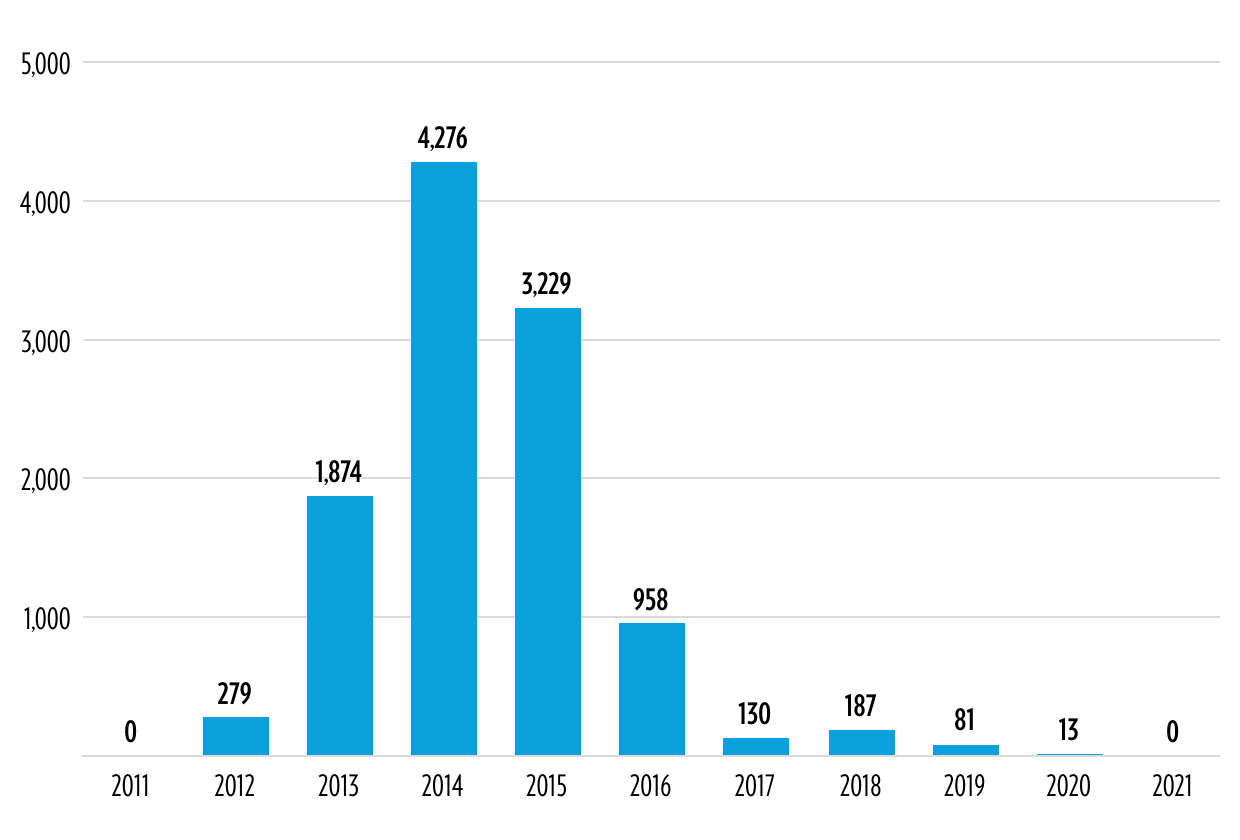

As the violence rapidly escalated in the fall of 2012, so did civilian casualties and displacement. At the same time, dissent began to mount among SyAAF officers and pilots, some of whom refused to carry out bombing missions against their fellow Syrians. Despite the tight control exercised by the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Services, we were able to individually identify at least 165 pilots who defected from the SyAAF between 2011 and 2015. Of these former pilots, 73 percent defected in the first wave of SyAAF operations in 2012 and 2013. In addition, hundreds of ordinary air force officers and enlisted men defected throughout the country – some merely walking off their posts, while others escaped across frontlines or national borders.

Defection and Division

The early months of the war also unveiled the latent sectarian tensions inside of Syria’s nominally secular air corps. Of the 165 pilots who defected from the SyAAF between 2011 and 2015, all but one (99.4 percent) were identified by the research team as members of the majority Sunni sect. In contrast, 90.1 percent of the 144 active pilots shot down over the course of the conflict whose identities were confirmed hailed from the minority Alawite population – a sect that makes up approximately 10 to 13 percent of Syria’s population, according to scholars’ estimates.31 In practice, the SyAAF divided immediately and strictly according to sect. And as frontlines throughout the country increasingly formed along sectarian lines, Alawite pilots flew daily combat missions targeting almost exclusively Sunni-majority population centers.

These stark divisions within the SyAAF are unsurprising, considering the decades-long, systematic campaign of sectarian “stacking” implemented by the Assad regime. Sunni officers were effectively sidelined from leadership roles in the Syrian air force and other military branches after the Muslim Brotherhood insurgency and Hama uprising in 1982. Indeed, painstaking research by Hicham Bou Nassif, who interviewed military defectors outside of Syria, revealed that on the eve of the uprising, key military leadership positions – particularly within Syria’s Praetorian, Special Forces and Intelligence units – had been systematically stacked with Alawite and other minority officers.32

Our reconstruction of command positions within the SyAAF follows a similar pattern: on the eve of the Syrian revolution, Alawite officers held 79 percent of all division, brigade and squadron commands inside the Syrian air force. Only one brigade was headed by a Sunni general officer, who was arrested in 2013 and now resides outside of the country. Over the course of the civil war, only one Sunni person (who was of Palestinian origin) was placed in command of a major SyAAF formation. As the Syrian regime felt increasingly beleaguered by a widening uprising, the remaining Sunni officers came under greater suspicion.

Sustaining Operations (2013–2015)

Because of the divisions at the start of the conflict, the Syrian air force went into action as a narrower, more sectarian force. Early on, the SyAAF struggled to sustain operations in the face of widespread defections, logistics challenges and mounting combat losses. To bolster their efforts, Russia provided the SyAAF with significant assistance, including pilot training, upgrade packages for aircrafts, weapons deliveries, and spare parts.33 In late 2013, an Iranian-supported offensive to regain access to Aleppo allowed for the resumption of work at the SyAAF’s principal maintenance and overhaul facility, which would reinstate and upgrade dozens of Su-22 and L-39 jets over the next two years (the latter of which received B-8 rocket pods, while its pilots were equipped with night-vision equipment).34 Meanwhile, Syrian officers scoured military depots across the former Soviet Union to recover much-needed spare parts.

However, despite the influx of Russian and Iranian support, three years of operations took a heavy toll on Syria’s air force. Prior to Russia’s intervention in the war in September 2015, the SyAAF had lost 120 out of its initial 535 airframes in combat, mostly due to ground fire, man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS) and equipment failures. As a consequence, the burden of most SyAAF operations rested on a few dozen operational airframes scattered across six bases, primarily in central Syria. The rising number of derelict airframes littering Syrian air bases, cannibalized for parts, testifies to the effort to keep the SyAAF’s few combat-ready airframes afloat.

To reduce risks to their remaining fleet, SyAAF pilots would fly outside of the range of the opposition’s anti-aircraft weapons, releasing unguided munitions and barrel bombs from above 4,000 meters in the air. This tactic further reduced the already abysmal precision of Syria’s ordnance. Desperation also led to creativity: one witness described an aborted attempt by the Syrian Scientific Research Center (SSRC) – the country’s secretive weapons research organization – to reconfigure aged MiG-21 jets into remote-controlled suicide aircraft. Only one of the reconfigured jets crashed into a busy market in opposition-held Ariha in August 2015.35 The program was eventually discontinued, as it was considered both too expensive and impractical.

Insurgent offensives against Syrian air bases also re-shaped the SyAAF’s entire order of battle. Over the course of the conflict, opposition forces have overtaken five air bases, while others were either surrounded or threatened by artillery and anti-tank guided missile (ATGM) fire. The capture of Jirah and Mennegh air bases in 2013 – two locations used for training fighter and helicopter pilots – greatly affected the SyAAF’s ability to replace pilot losses. While a share of Syria’s Mi-8/17 transport helicopter fleet was converted into so-called “barrel bombers” that flew primarily from Hama Air Base as well as newly established forward-operating bases across Northwest Syria, the remaining helicopters were essential to servicing far-flung loyalist pockets in the country’s central and eastern provinces. In enclaves such as Deir Ezzor, which spent years under continuous threat from Islamic State assaults, discretion concerning who and what would be transported via the air bridge also provided a lucrative opportunity for the personal enrichment of base commanders and senior officers.

Operational Patterns (2016–2020)

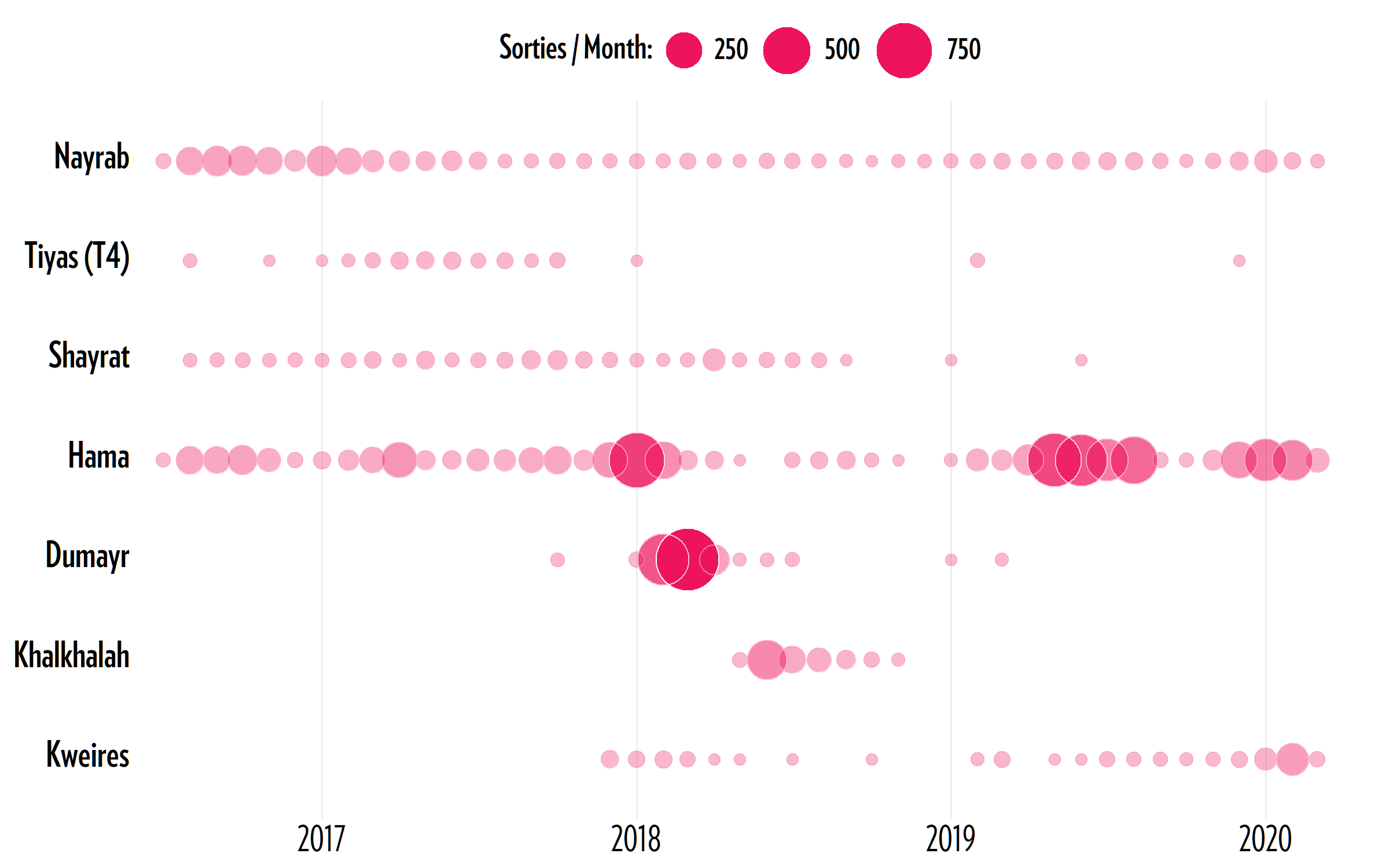

As a consequence of the continual loss of men, military equipment and facilities, the SyAAF came to rely on only a few dozen airframes flying out of a handful of bases. Using air tracking data recorded by early warning systems and air observers over the course of the war, we are able to trace the patterns of the SyAAF’s operations. The data reveals that, in the face of attrition, the SyAAF effectively consolidated its efforts to maintain a small operational fleet out of a few key bases. Just six air bases – Hama, Shayrat, Sayqal, Tiyas, Nayrab, and Dumayr – accounted for 91 percent of all SyAAF combat sorties between 2016 and 2021. According to interviews conducted with former SyAAF staff officers, air bases would commonly be responsible for supporting nearby ground operations, leading to increased activity in bases surrounded by regions with heavy fighting. In particular, the outsized role of Hama Air Base – which accounts for 38 percent of all combat sorties since 2016 – is best explained by its proximity to opposition-held territory in Northwest Syria.

Share of Combat Sorties by Air Base (2016–2021)

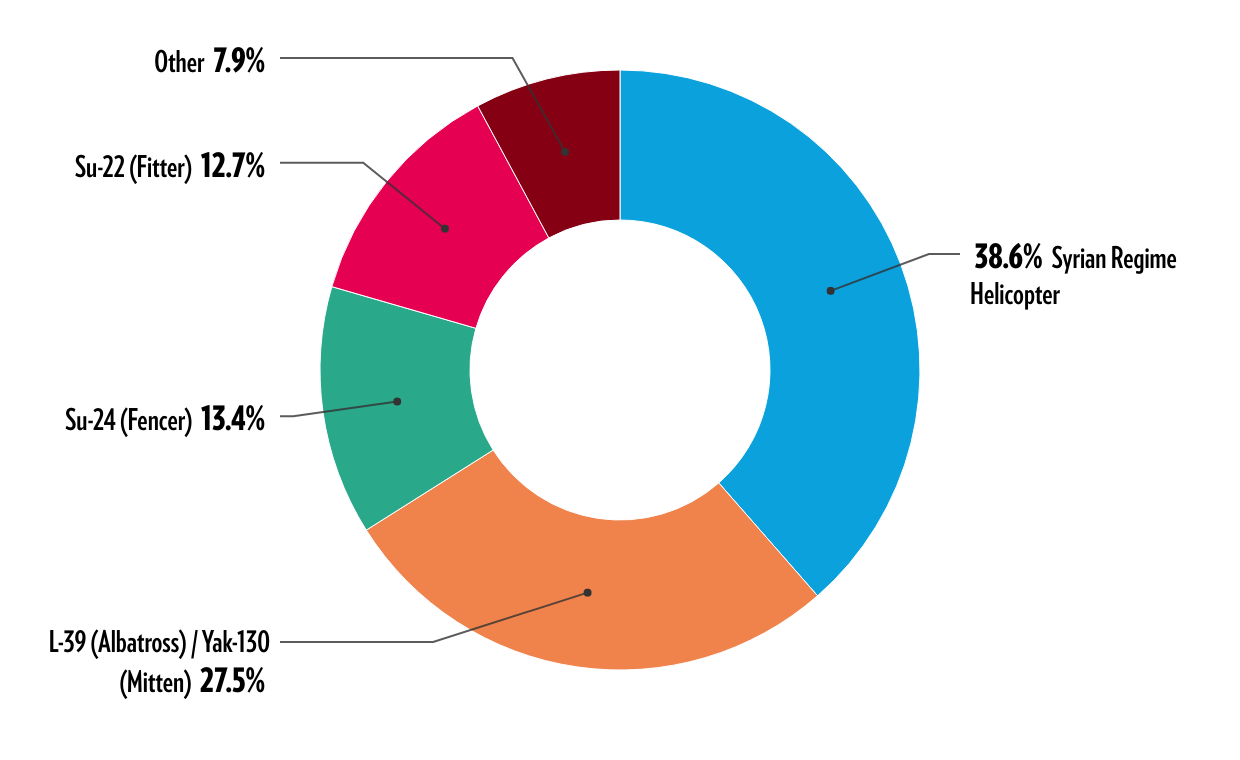

Share of Air Activity by Aircraft Type (2016–2021)

In addition to its size and central location, Hama also serves as a primary operational hub for the workhorses of the SyAAF: a small fleet of 5-10 Mi-8/17 transport helicopters configured to carry barrel bombs, as well as a squadron of L-39 light attack aircraft capable of nighttime operations. Combined, these two aircraft types account for approximately two-thirds of all SyAAF combat sorties since 2016. Besides their pace of operations, these two SyAAF elements further distinguish themselves by their mobility: while most squadrons have remained fixed to their air bases following consolidation early in the war, the research team has traced the movement of the two detachments of Mi-8/17 and L-39 airframes across multiple theaters in western, central and southern Syria since 2016. These movements suggest close integration with the Syrian Army’s few remaining offensive ground troops.

L-39 Activity Across Air Bases

Since their initial appearance in 2012, the small detachment of modified SyAAF Mi-8/17 helicopters carrying explosive and shrapnel-filled barrels has caused untold devastation, particularly in Northwest Syria. Responsible for almost 40 percent of observed SyAAF combat sorties since 2016, Syrian air force helicopters have also been tied to dozens of chemical attacks involving improvised chlorine-filled munitions, including the 7 April 2018 attack on Duma. According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, barrel bombs have killed at least 11,000 civilians over the course of the war, injuring tens of thousands more and leaving entire populations traumatized. In the latest government-led offensive against Northwest Syria in 2019 and 2020 alone, local responders recorded at least 908 barrel bomb attacks in the region, which strongly correlated with observed Mi-8/17 departures from the nearby Hama Air Base and smaller heliports. The analysis of flight tracking data and satellite imagery, combined with testimonies from air observers who could identify pilots by their voice and individual code names, suggests that the associated squadron consists of no more than six to ten airframes. Its rebasing patterns, as well as intercepted radio communications, indicate that the squadron is closely affiliated with the so-called “Tiger Forces” – one of the few remaining Syrian military formations capable of leading offensive operations. While active since late 2012, data shows that pilots from this squadron had recently been equipped with night-vision equipment, making their sorties even more deadly.

Civilian Deaths Due to Barrel Bombs since 2011

In addition to helicopters carrying barrel bombs, most Syrian air operations in recent years have relied heavily on a mobile squadron of L-39 jets. While these light attack aircraft have received considerably less attention than the notorious barrel bombers, they were nonetheless responsible for more than a quarter of all recorded SyAAF flight activity since 2016 – more than the efforts of the Su-22 and Su-24 fleets combined. According to reporting by Tom Cooper, these light attack aircraft were refitted to carry more potent munitions, and their pilots outfitted with night-vision equipment. Indeed, activity data confirms that L-39s are the only jets in the Syrian air force that consistently operate after nightfall.

L-39 and Su-22 Activity by Time of Day (2016–2021)

Helicopter Activity by Time of Day (2017–2019)

They are also the only detachment of jets which regularly relocate to different air bases in order to support ground operations. Flight activity data shows how, similar to the patterns of the Mi-8/17 detachment dropping barrel bombs, a small number of L-39 have trailed Russian-backed offensives of the Tiger Forces since at least 2016, shifting air bases almost in parallel with the helicopter detachment.

In addition, the SyAAF relies on its fleet of Su-22 and Su-24 aircraft, which operate out of the Sayqal, Shayrat, Dumayr, and Tiyas air bases in central Syria, to act as long-range strike bombers. At their operational peak during the 2018 loyalist offensive against eastern Ghouta, these fleets were able to generate 160 and 130 sorties per week, respectively. However, for most of the war, weekly rates of combat sorties in support of operations was only half of that peak. The data also qualifies claims made by American officials in the aftermath of US airstrikes against Shayrat Air Base following a chemical attack in April 2017. At the time, US Secretary of Defense James Mattis claimed that the cruise missile strike had destroyed “20 percent of the Syrian government’s operational aircraft” and that the base had “lost the ability to refuel or rearm aircraft.”36 However, flight activity data shows no decline in the rate of Su-22 aircraft sorties in the aftermath of the attack, suggesting that most combat-ready airframes had either survived the strike or that the lost aircraft had been replaced. Shayrat Air Base was able to resume its operations within a few weeks of the strike.

The flight data also reveals that older jet models in Syrian air operations have increasingly fallen out of use. At the start of the war, the SyAAF already considered its ageing fleet of MiG-21 jets effectively obsolete, and worked to repurpose at least 17 of the airframes as remote-controlled suicide jets. In late 2020, at least 79 discarded MiG-21s could be found parked on the periphery of Syrian air bases – we have concluded that another 28 had been destroyed in combat. While our team was able to visually confirm that at least four jets remain in service at Hama Air Base, their activity has accounted for no more than two percent of all combat sorties since 2016. While the MiG-23 proved more resilient throughout the war, the last active MiG-23 detachment operating in Northwest Syria – the 678th Squadron based out of Hama Air Base – has accounted for no more than four percent of all flights over the region in recent battles.

Despite these adverse circumstances, Syria’s air force has sustained, and even at times increased, its pace of operations over the course of the war. While data is scarce for the initial years of the conflict, flight tracking shows that the SyAAF consistently generated more than 1,000 sorties per month against opposition-held regions between 2016 and 2020. At its peak in early 2018, the Syrian air force was even able to generate that number of sorties in a single week in support of the loyalist offensive against the Eastern Ghouta pocket. Further, the tracking data suggests that in the aftermath of the territorial defeat of the Islamic State in Syria in late 2017, the SyAAF was able to focus additional air assets against opposition-held regions, almost doubling their weekly sorties in support of loyalist offensives in the spring of 2018 and throughout 2019.

Policy Deliberations

Policy Deliberations and No-Fly Zones

As successive international mediation efforts failed and the situation deteriorated across Syria in the summer of 2012, Western policymakers were forced to consider the prospect and practicality of containing the violence, possibly through military force. The international response to the Libyan uprising offered an immediate example. A year earlier, the UN Security Council had authorized a NATO-led mission to establish a no-fly zone in Libya. In the space of a few months, the mission had succeeded in halting the loyalist offensive against the country’s second-largest city, Benghazi, and eventually reversed the tide of the fighting on the ground.

For some US policymakers, the lessons of the Libyan intervention spoke against involvement in Syria: Russia and China had publicly denounced the West for executing a regime-change operation under the guise of humanitarian protection, and vowed not to allow a repeat in the UN Security Council. The United States also realized that, even with the backing of coalition partners, any mission at this scale would depend almost entirely on American capabilities. Invariably, US involvement would create expectations that Washington would support the ousting of Bashar Al-Assad, just as the Libya mission had eventually led to the overthrow and death of Muammar Gaddafi. While the Obama administration publicly stood by its call for Assad to step down from power, the quiet consensus in Washington had begun to shift over the previous year. For example, in one workshop conducted by the RAND Corporation in December 2013, a group of prominent experts from US intelligence and policy communities concluded that, of the possible futures considered for the conflict in Syria, the worst outcome for US strategic interests would be the collapse of the Syrian regime.37 The words “catastrophic success” – an imagined scenario in which the Assad regime would be replaced by warring Islamist militias – would often be bandied around the White House halls.

However, many officials and commentators remained frustrated with the continued inaction of the Obama administration, especially after reports of chemical weapons use surfaced in early 2013. In an exchange that captured the prevailing concerns at the time, leading US senators demanded that Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Martin Dempsey provide his assessment on the costs and benefits of potential military options in Syria. In his response to Senators Levin and McCain the next day, Dempsey outlined five military missions that the Pentagon had considered: a mission to “train, advise and assist the opposition”; a series of “limited stand-off strikes” against Syrian military positions; the establishment of a “no-fly zone” or a “buffer zone” for the protection of civilians; as well as a comprehensive intervention to “control Syria’s chemical weapons”. Each of these options was priced in terms of the likely costs in US dollars and military investment. Seeing few upsides to any of them, Dempsey wrote that he supported “a regional approach that would isolate the conflict to prevent regional destabilization and weapons proliferation,” as well as efforts to strengthen a “moderate opposition”. The risks inherent in this passive approach were not outlined.38

The five options outlined in Dempsey’s letter drew immediate pushback from a number of experts around Washington, who largely condemned what they saw as the Chairman’s excessive focus on the risk of intervention over the likely cost of leaving the conflict to fester. Several respected defense analysts, including Anthony Cordesman from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, also questioned the administration’s assessment that establishing a no-fly zone would require the comprehensive suppression of Syrian air defenses and would yield limited effects on the ground. During briefings in July 2013, the Institute for the Study of War assessed that the dilapidated state of the SyAAF meant that the US could have effectively wiped out Syria’s air force by using multiple standoff strikes against key air bases at relatively low cost or risk to American personnel.39

The question of US involvement in Syria finally came to a head following the chemical attacks on the outskirts of Damascus on 21 August, 2013, which left at least 1,400 civilians dead. A year earlier, the Obama administration had repeatedly warned the Syrian government that the use or proliferation of chemical weapons would cross a figurative “red line” – and lead the United States to reconsider its non-interventionist stance on the conflict. In response to the massacre, the US military prepared a package of airstrikes against at least 50 targets across the country, including key SyAAF facilities.40 In the end, the US attack was first delayed, and eventually called off entirely. Following a deal brokered between the American and Russian presidents on the sidelines of the 2013 G8 summit, Syria was forced to declare and surrender its chemical stockpile in order to avert American airstrikes.

International Intervention in the Syrian Conflict

While it seemed that the time for US intervention had passed, less than a year after the “red line” moment, the US Air Force would launch an intense campaign of airstrikes inside Syria. The intervention in Syria was part of a multinational coalition tasked with combating the Islamic State group, which had taken control of parts of central, northern and eastern Syria. In order to avoid getting drawn into the war itself, coalition jets would avoid any unnecessary confrontation with the SyAAF, including in instances when Syrian helicopters would strike against America’s local Kurdish partner forces, as they did in Hasakeh in 2016. However, even the more restrictive rules of engagement allowed US pilots to defend themselves, leading to a series of high-risk, mid-air scrapes between American, Russian and Syrian jets. Finally, repeat SyAAF provocations against what they considered an illegitimate foreign presence culminated in the US shootdown of a Syrian Su-22 jet in June 2017.41

In the aftermath, American and Russian officials instituted a de-facto demarcation of the country’s airspace along the Euphrates River. In doing so, the United States inadvertently imposed a safe zone over a third of the country. While Syrian helicopters and planes were still allowed to shuttle to government-held regions, the American intervention had nonetheless succeeded in effectively shielding millions of civilians living in Northeast Syria from further predation. As the agreement excluded most areas held by opposition forces, the arrangement effectively established the “condominium” of air power in the Syrian conflict that would give the SyAAF near-total freedom over opposition-held territories in western Syria.

The only power in the position to directly challenge the Syrian air force is neighboring Turkey. However, Ankara was hesitant to act after the Turkish shootdown of a Russian jet in the fall of 2015 triggered a diplomatic crisis. While Turkish jets had supported anti-Islamic State operations in northern Aleppo, it was only in the spring of 2020, when a loyalist offensive in Northwest Syria threatened to drive millions of refugees across the Turkish border, that Ankara established a militarily-defended buffer zone against Syrian government forces. In the process, the Turkish military shot down two Syrian helicopters and three jets using shoulder-fired missiles manned by the Turkish Special Forces on the ground and F-16s fired from inside Turkish airspace. Turkish forces also launched attacks against nearby Syrian airfields. By striking at SyAAF targets from inside Turkey and from the ground, Ankara managed to halt the loyalist offensive without directly challenging Russia’s air superiority in western Syria. While Syrian jets have occasionally tried to challenge the subsequently established ceasefire line, no barrel bombs have since been dropped on opposition-held regions.

At the same time, neighboring Israel has also escalated its air campaign against Iranian targets throughout Syria. According to media reports, the Israeli Air Force has executed hundreds of airstrikes against Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and Hezbollah-affiliated positions since 2017. In 2020 alone, the Israeli military acknowledged leading 50 strike missions across the Syrian border,42 ranging as far inland as Latakia and Deir Ezzor, and striking at some of Syria’s most sensitive military infrastructure hosting Iranian advisors. During these raids, Israel only lost one airframe to Syrian air defenses. The success of the Turkish and Israeli campaigns give credence to earlier arguments that expansive attritional strikes against Syria were indeed possible at relatively low costs. When the United States, France and the United Kingdom launched attacks against Syrian chemical weapons and SyAAF facilities in 2017 and 2018, they also reported not losing a single cruise missile and managed to avoid being drawn into the wider war.

- play_arrow The SyAAF at War:Introduction